Seamus Heaney

Seamus Heaney Poems

Late August, given heavy rain and sun

For a full week, the blackberries would ripen.

At first, just one, a glossy purple clot

Among others, red, green, hard as a knot.

...

My father worked with a horse-plough,

His shoulders globed like a full sail strung

Between the shafts and the furrow.

The horse strained at his clicking tongue.

...

I sat all morning in the college sick bay

Counting bells knelling classes to a close.

At two o'clock our neighbors drove me home.

...

Her scarf a la Bardot,

In suede flats for the walk,

She came with me one evening

For air and friendly talk.

...

All year the flax-dam festered in the heart

Of the townland; green and heavy headed

Flax had rotted there, weighted down by huge sods.

Daily it sweltered in the punishing sun.

...

And some time make the time to drive out west

Into County Clare, along the Flaggy Shore,

In September or October, when the wind

And the light are working off each other

...

We have no prairies

To slice a big sun at evening--

Everywhere the eye concedes to

Encrouching horizon,

...

The pockets of our greatcoats full of barley...

No kitchens on the run, no striking camp...

We moved quick and sudden in our own country.

The priest lay behind ditches with the tramp.

...

She taught me what her uncle once taught her:

How easily the biggest coal block split

If you got the grain and the hammer angled right.

...

Air from another life and time and place,

Pale blue heavenly air is supporting

A white wing beating high against the breeze,

...

I

To-night, a first movement, a pulse,

As if the rain in bogland gathered head

...

I was six when I first saw kittens drown.

Dan Taggart pitched them, 'the scraggy wee shits',

Into a bucket; a frail metal sound,

...

It is December in Wicklow:

Alders dripping, birches

Inheriting the last light,

The ash tree cold to look at.

...

So winter closed its fist

And got it stuck in the pump.

The plunger froze up a lump

...

My 'place of clear water,'

the first hill in the world

where springs washed into

the shiny grass

...

The tightness and the nilness round that space

when the car stops in the road, the troops inspect

its make and number and, as one bends his face

...

There, in the corner, staring at his drink.

The cap juts like a gantry's crossbeam,

Cowling plated forehead and sledgehead jaw.

Speech is clamped in the lips' vice.

...

for Michael Longley

As a child, they could not keep me from wells

And old pumps with buckets and windlasses.

...

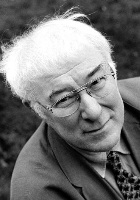

Seamus Heaney Biography

Seamus Justin Heaney was an Irish poet, playwright, translator and lecturer, and the recipient of the 1995 Nobel Prize in Literature. In the early 1960s he became a lecturer in Belfast after attending university there, and began to publish poetry. He lived in Sandymount, Dublin from 1972 until his death. Heaney was a professor at Harvard from 1981 to 1997 and its Poet in Residence from 1988 to 2006. From 1989 to 1994 he was also the Professor of Poetry at Oxford and in 1996 was made a Commandeur de l'Ordre des Arts et Lettres. Other awards that Heaney received include the Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prize (1968), the E. M. Forster Award (1975), the PEN Translation Prize (1985), the Golden Wreath of Poetry (2001), T. S. Eliot Prize (2006) and two Whitbread Prizes (1996 and 1999). In 2012, he was awarded the Lifetime Recognition Award from the Griffin Trust For Excellence In Poetry. Heaney's literary papers are held by the National Library of Ireland. Robert Lowell called him "the most important Irish poet since Yeats" and many others, including the academic John Sutherland, have echoed the sentiment that he was "the greatest poet of our age". Robert Pinsky has stated that "with his wonderful gift of eye and ear Heaney has the gift of the story-teller". Upon his death in 2013, The Independent described him as "probably the best-known poet in the world". Early Life Heaney was born on 13 April 1939, at the family farmhouse called Mossbawn, between Castledawson and Toomebridge in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland; he was the first of nine children. In 1953, his family moved to Bellaghy, a few miles away, which is now the family home. His father, Patrick Heaney (d. October 1986), was the eighth child of ten born to James and Sarah Heaney. Patrick was a farmer, but his real commitment was to cattle-dealing, to which he was introduced by the uncles who had cared for him after the early death of his own parents. Heaney's mother, Margaret Kathleen McCann (1911–1984),[12] who bore nine children, came from the McCann family, whose uncles and relations were employed in the local linen mill, and whose aunt had worked as a maid for the mill owner's family. Heaney commented on the fact that his parentage thus contained both the Ireland of the cattle-herding Gaelic past and the Ulster of the Industrial Revolution; he considered this to have been a significant tension in his background. Heaney initially attended Anahorish Primary School, and when he was twelve years old, he won a scholarship to St. Columb's College, a Roman Catholic boarding school situated in Derry. Heaney's brother, Christopher, was killed in a road accident at the age of four while Heaney was studying at St. Columb's. The poems "Mid-Term Break" and "The Blackbird of Glanmore" focus on his brother's death. Death and Reaction Heaney died in the Blackrock Clinic in Dublin on 30 August 2013, aged 74, following a short illness. After a fall outside a restaurant in Dublin, he entered hospital the night before his death for a medical procedure but died at 7:30 the following morning before it took place. His funeral was held in Donnybrook, Dublin, on the morning of 2 September 2013, and he was buried in the evening at his home village of Bellaghy, in the same graveyard as his parents, young brother, and other family members. His son Michael revealed at the funeral mass that his father's final words, "Noli timere", were texted to his wife, Marie, minutes before he died. A crowd of 81,553 spectators applauded Heaney for three minutes at an All-Ireland Gaelic football semi-final match on September 1. His funeral was broadcast live the following day on RTÉ television and radio, and was streamed internationally at RTÉ's website, while RTÉ Radio 1 Extra transmitted a continuous broadcast, from 8 a.m. to 9:15 p.m. on the day of the funeral, of his Collected Poems album, recorded by Heaney himself in 2009. His poetry collections sold out rapidly in Irish bookshops immediately following his death. Many tributes were paid to Heaney. President Michael D. Higgins said: "...we in Ireland will once again get a sense of the depth and range of the contribution of Seamus Heaney to our contemporary world, but what those of us who have had the privilege of his friendship and presence will miss is the extraordinary depth and warmth of his personality...Generations of Irish people will have been familiar with Seamus' poems. Scholars all over the world will have gained from the depth of the critical essays, and so many rights organisations will want to thank him for all the solidarity he gave to the struggles within the republic of conscience." Higgins also appreared live from Áras an Uachtaráin on the Nine O'Clock News in a five-minute segment in which he paid tribute to Heaney. Bill Clinton, former President of the United States, said: "Both his stunning work and his life were a gift to the world. His mind, heart, and his uniquely Irish gift for language made him our finest poet of the rhythms of ordinary lives and a powerful voice for peace...His wonderful work, like that of his fellow Irish Nobel Prize winners Shaw, Yeats, and Beckett, will be a lasting gift for all the world." José Manuel Barroso, European Commission president, said: "I am greatly saddened today to learn of the death of Seamus Heaney, one of the great European poets of our lifetime...The strength, beauty and character of his words will endure for generations to come and were rightly recognised with the Nobel Prize for Literature." Harvard University issued a statement: "We are fortunate and proud to have counted Seamus Heaney as a revered member of the Harvard family. For us, as for people around the world, he epitomised the poet as a wellspring of humane insight and artful imagination, subtle wisdom and shining grace. We will remember him with deep affection and admiration." Poet Michael Longley, a close friend of Heaney, said: "I feel like I've lost a brother". Thomas Kinsella was shocked but John Montague said he'd known for some time the poet was not well. Playwright Frank McGuinness called Heaney "the greatest Irishman of my generation: he had no rivals". Colm Tóibín wrote: "In a time of burnings and bombings Heaney used poetry to offer an alternative world". Gerald Dawe said he was "like an older brother who encouraged you to do the best you could do". Theo Dorgan said "[Heaney's] work will pass into permanence. Everywhere I go there is real shock at this. Seamus was one of us", while Heaney's publisher Faber and Faber noted that "his impact on literary culture is immeasurable." Playwright Tom Stoppard said, "Seamus never had a sour moment, neither in person nor on paper". Andrew Motion, a former UK Poet Laureate and friend of Heaney, called him "a great poet, a wonderful writer about poetry, and a person of truly exceptional grace and intelligence". Work Upon his death, Heaney's books made up two-thirds of the sales of living poets in the UK. His work often deals with the local surroundings of Ireland, particularly in Northern Ireland, where he was born. Speaking of his early life and education, he commented "I learned that my local County Derry experience, which I had considered archaic and irrelevant to 'the modern world' was to be trusted. They taught me that trust and helped me to articulate it." Death of a Naturalist (1966) and Door into the Dark (1969) mostly focus on the detail of rural, parochial life. Allusions to sectarian difference, widespread in Northern Ireland through his lifetime, can be found in his poems. His books Wintering Out (1973) and North (1975) seek to interweave commentary on 'The Troubles' with a historical context and wider human experience. While some critics accused Heaney of being "an apologist and a mythologizer" of the violence, Blake Morrison suggests the poet "has written poems directly about the Troubles as well as elegies for friends and acquaintances who have died in them; he has tried to discover a historical framework in which to interpret the current unrest; and he has taken on the mantle of public spokesman, someone looked to for comment and guidance... Yet he has also shown signs of deeply resenting this role, defending the right of poets to be private and apolitical, and questioning the extent to which poetry, however 'committed,' can influence the course of history." Shaun O'Connell in the New Boston Review notes that "those who see Seamus Heaney as a symbol of hope in a troubled land are not, of course, wrong to do so, though they may be missing much of the undercutting complexities of his poetry, the backwash of ironies which make him as bleak as he is bright." O'Connell notes in his Boston Review critique of Station Island: "Again and again Heaney pulls back from political purposes; despite its emblems of savagery, Station Island lends no rhetorical comfort to Republicanism. Politic about politics, Station Island is less about a united Ireland than about a poet seeking religious and aesthetic unity". Heaney is described by critic Terry Eagleton as "an enlightened cosmopolitan liberal", refusing to be drawn. Eagleton suggests: "When the political is introduced... it is only in the context of what Heaney will or will not say." Reflections on what Heaney identifies as "tribal conflict", favour the description of people's lives and their voices, drawing out the 'psychic landscape'. His collections often recall the assassination of his family members and close friends, lynchings and bombings. Colm Tóibín wrote, "throughout his career there have been poems of simple evocation and description. His refusal to sum up or offer meaning is part of his tact." Heaney published “Requiem for the Croppies”, a poem that commemorates the Irish rebels of 1798, on the 50th anniversary of the 1916 Easter Rising. He read the poem to both Catholic and Protestant audiences in Ireland. He commented "To read ‘'Requiem for the Croppies'’ wasn't to say ‘up the IRA’ or anything. It was silence-breaking rather than rabble-rousing.” He stated “You don't have to love it. You just have to permit it.” He turned down the offer of laureateship partly for political reasons, commenting "I’ve nothing against the Queen personally: I had lunch at the Palace once upon a time". He stated that his "cultural starting point" was "off centre". A much-quoted statement was when he objected to being included in The Penguin Book of Contemporary British Poetry (1982), despite being born in Northern Ireland. His response to being included in the British anthology was delivered in his poem, An Open Letter: "Don't be surprised if I demur, for, be advised My passport's green. No glass of ours was ever raised To toast The Queen." He was concerned, as a poet and a translator, with the English language itself as it is spoken in Ireland but also as spoken elsewhere and in other times; the Anglo-Saxon influences in his work and study are strong. Critic W. S. Di Piero noted "Whatever the occasion, childhood, farm life, politics and culture in Northern Ireland, other poets past and present, Heaney strikes time and again at the taproot of language, examining its genetic structures, trying to discover how it has served, in all its changes, as a culture bearer, a world to contain imaginations, at once a rhetorical weapon and nutriment of spirit. He writes of these matters with rare discrimination and resourcefulness, and a winning impatience with received wisdom." Heaney's first translation came with the Irish lyric poem "Buile Suibhne", published as Sweeney Astray: A Version from the Irish (1984), a character and connection taken up in Station Island (1984). Heaney's prize-winning translation of Beowulf (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000, Whitbread Book of the Year Award) was seen as ground-breaking in its use of modern language melded with the original Anglo-Saxon 'music'. His works of drama includes The Cure at Troy: A Version of Sophocles' Philoctetes (1991). Heaney's 2004 play The Burial at Thebes makes parallels between Creon with the foreign policies of the Bush administration. Heaney's engagement with poetry as a necessary engine for cultural and personal change, is reflected in his prose works The Redress of Poetry (1995) and Finders Keepers: Selected Prose, 1971–2001 (2002). "When a poem rhymes," Heaney wrote, "when a form generates itself, when a metre provokes consciousness into new postures, it is already on the side of life. When a rhyme surprises and extends the fixed relations between words, that in itself protests against necessity. When language does more than enough, as it does in all achieved poetry, it opts for the condition of overlife, and rebels at limit." He expands: "The vision of reality which poetry offers should be transformative, more than just a printout of the given circumstances of its time and place". Often overlooked and underestimated in the direction of his work is his profound poetic debts to and critical engagement with 20th-century Eastern European poets, and in particular Nobel laureate Czesław Miłosz. Heaney's work is used extensively on school syllabi internationally, including the anthologies The Rattle Bag (1982) and The School Bag (1997) (both edited with Ted Hughes). Originally entitled The Faber Book of Verse for Younger People on the Faber contract, Hughes and Heaney decided the The Rattle Bag's main purpose was to offer enjoyment to the reader: "Arbitrary riches". Heaney commented "the book in our heads was something closer to The Fancy Free Poetry Supplement". It included work that they would have liked to encountered sooner as well as nonsense rhymes, ballad-type poems, riddles, folk songs and rhythmical jingles. Much familiar canonical work was not included, since they took it for granted that their audience would know the standard fare. Fifteen years later The School Bag aimed at something different. The foreword stated that they wanted "less of a carnival, more like a checklist." It included poems in English, Irish, Welsh, Scots and Scots Gaelic, together with work reflecting the African-American experience. Heaney's work is also the basis for a collaboration with Mohammed Fairouz who composed a choral setting of Heaney's poems.)

The Best Poem Of Seamus Heaney

Blackberry-Picking

Late August, given heavy rain and sun

For a full week, the blackberries would ripen.

At first, just one, a glossy purple clot

Among others, red, green, hard as a knot.

You ate that first one and its flesh was sweet

Like thickened wine: summer's blood was in it

Leaving stains upon the tongue and lust for

Picking. Then red ones inked up and that hunger

Sent us out with milk cans, pea tins, jam-pots

Where briars scratched and wet grass bleached our boots.

Round hayfields, cornfields and potato-drills

We trekked and picked until the cans were full

Until the tinkling bottom had been covered

With green ones, and on top big dark blobs burned

Like a plate of eyes. Our hands were peppered

With thorn pricks, our palms sticky as Bluebeard's.

We hoarded the fresh berries in the byre.

But when the bath was filled we found a fur,

A rat-grey fungus, glutting on our cache.

The juice was stinking too. Once off the bush

The fruit fermented, the sweet flesh would turn sour.

I always felt like crying. It wasn't fair

That all the lovely canfuls smelt of rot.

Each year I hoped they'd keep, knew they would not.

Seamus Heaney Comments

Very sad to hear of the death of Seamus Heaney. He was a brilliant poet and a real and kind gentleman. His talent and persona will be greatly missed throughout the world.

He died nearly a week ago.Amazing man.I would have thought you may have noticed that fact poemhunter.

I so wish that I had had the privilege meeting and perhaps to have had a chat with this iconic and incredible human being. Maybe in the next life.

I just viewed a very offensive video of the late iconic poet on youtube when I visited the website to view his last appearance titled 'last appearance of Seamus Heaney'. I was horrified! I can't even believe that anyone could do it.

I am doing my research on Heaney's first collection entitled Death of a Naturalist from a deconstructive angle of perception.

I'm trying to find the text of a Heaney poem named POEM (! ! !) , which of course isn't easy. It doesn't come up under Search, and isn't listed in the top 50 of his poems which seem to be all given in this listing. What next?

i hate poemssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssss

in his first collections heaney is fascinated with the soil as he can perceive a mysterious life force in it. He uses many words to refer to it: slime, muck, mush. All of them describe a soil that is wetting and become less solid: this is a metaphor for sexual life, where the soil is the female element responding to a male one.