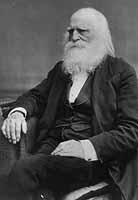

William Cullen Bryant

William Cullen Bryant Poems

To him who in the love of nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language; for his gayer hours

She has a voice of gladness, and a smile

...

Ay, thou art for the grave; thy glances shine

Too brightly to shine long; another Spring

Shall deck her for men's eyes---but not for thine---

Sealed in a sleep which knows no wakening.

...

Whither, midst falling dew,

While glow the heavens with the last steps of day

Far, through their rosy depths, dost thou pursue

Thy solitary way?

...

The melancholy days are come, the saddest of the year,

Of wailing winds, and naked woods, and meadows brown and sere.

Heaped in the hollows of the grove, the autumn leaves lie dead;

They rustle to the eddying gust, and to the rabbit's tread;

...

'Oh father, let us hence--for hark,

A fearful murmur shakes the air.

The clouds are coming swift and dark:--

...

It is a sultry day; the sun has drank

The dew that lay upon the morning grass,

There is no rustling in the lofty elm

That canopies my dwelling, and its shade

...

Yet one smile more, departing, distant sun!

One mellow smile through the soft vapoury air,

Ere, o'er the frozen earth, the loud winds ran,

Or snows are sifted o'er the meadows bare.

...

The groves were God's first temples. Ere man learned

To hew the shaft, and lay the architrave,

And spread the roof above them,---ere he framed

The lofty vault, to gather and roll back

...

The time has been that these wild solitudes,

Yet beautiful as wild, were trod by me

Oftener than now; and when the ills of life

...

Is this a time to be cloudy and sad,

When our mother Nature laughs around;

When even the deep blue heavens look glad,

And gladness breathes from the blossoming ground?

...

When beechen buds begin to swell,

And woods the blue-bird's warble know,

The yellow violet's modest bell

Peeps from last-year's leaves below.

...

The day had been a day of wind and storm;--

The wind was laid, the storm was overpast,--

And stooping from the zenith, bright and warm

Shone the great sun on the wide earth at last.

...

The quiet August noon has come,

A slumberous silence fills the sky,

The fields are still, the woods are dumb,

In glassy sleep the waters lie.

...

O constellations of the early night,

That sparkled brighter as the twilight died,

And made the darkness glorious! I have seen

Your rays grow dim upon the horizon's edge,

...

Ay, thou art welcome, heaven's delicious breath!

When woods begin to wear the crimson leaf,

And suns grow meek, and the meek suns grow brief

And the year smiles as it draws near its death.

...

Stay yet, my friends, a moment stay—

Stay till the good old year,

So long companion of our way,

Shakes hands, and leaves us here.

...

Oh! could I hope the wise and pure in heart

Might hear my song without a frown, nor deem

My voice unworthy of the theme it tries,--

I would take up the hymn to Death, and say

...

Love's worshippers alone can know

The thousand mysteries that are his;

His blazing torch, his twanging bow,

His blooming age are mysteries.

...

William Cullen Bryant Biography

an American romantic poet, journalist, and long-time editor of the New York Evening Post. Bryant was born on November 3, 1794, in a log cabin near Cummington, Massachusetts; the home of his birth is today marked with a plaque. He was the second son of Peter Bryant, a doctor and later a state legislator, and Sarah Snell. His maternal ancestry traces back to passengers on the Mayflower; his father's, to colonists who arrived about a dozen years later. Bryant and his family moved to a new home when he was two years old. The William Cullen Bryant Homestead, his boyhood home, is now a museum. After just two years at Williams College, he studied law in Worthington and Bridgewater in Massachusetts, and he was admitted to the bar in 1815. He then began practicing law in nearby Plainfield, walking the seven miles from Cummington every day. On one of these walks, in December 1815, he noticed a single bird flying on the horizon; the sight moved him enough to write "To a Waterfowl". Bryant developed an interest in poetry early in life. Under his father's tutelage, he emulated Alexander Pope and other Neo-Classic British poets. The Embargo, a savage attack on President Thomas Jefferson published in 1808, reflected Dr. Bryant's Federalist political views. The first edition quickly sold out—partly because of the publicity earned by the poet's young age—and a second, expanded edition, which included Bryant's translation of Classical verse, was printed. The youth wrote little poetry while preparing to enter Williams College as a sophomore, but upon leaving Williams after a single year and then beginning to read law, he regenerated his passion for poetry through encounter with the English pre-Romantics and, particularly, William Wordsworth. Poetry Although "Thanatopsis", his most famous poem, has been said to date from 1811, it is much more probable that Bryant began its composition in 1813, or even later. What is known about its publication is that his father took some pages of verse from his son's desk and submitted them, along with his own work, to the North American Review in 1817. The Review was edited by Edward Tyrrel Channing at the time and, upon receiving it, read the poem to his assistant, who immediately exclaimed, "That was never written on this side of the water!" Someone at the North American joined two of the son's discrete fragments, gave the result the Greek-derived title Thanatopsis (meditation on death), mistakenly attributed it to the father, and published it. For all the errors, it was well-received, and soon Bryant was publishing poems with some regularity, including "To a Waterfowl" in 1821. On January 11, 1821, Bryant, still striving to build a legal career, married Frances Fairchild. Soon after, having received an invitation to address the Harvard University Phi Beta Kappa Society at the school's August commencement, Bryant spent months working on "The Ages," a panorama in verse of the history of civilization, culminating in the establishment of the United States. That poem led a collection, entitled Poems, which he arranged to publish on the same trip to Cambridge. For that book, he added sets of lines at the beginning and end of "Thanatopsis." His career as a poet was launched. Even so, it was not until 1832, when an expanded Poems was published in the U.S. and, with the assistance of Washington Irving, in Britain, that he won recognition as America's leading poet. His poetry has been described as being "of a thoughtful, meditative character, and makes but slight appeal to the mass of readers." Editorial Career Writing poetry could not financially sustain a family. From 1816 to 1825, he practiced law in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, and supplemented his income with such work as service as the town's hog reeve. Distaste for pettifoggery and the sometimes absurd judgments pronounced by the courts gradually drove him to break with the legal profession. With the help of a distinguished and well-connected literary family, the Sedgwicks, he gained a foothold in New York City, where, in 1825, he was hired as editor, first of the New-York Review, then of the United States Review and Literary Gazette. But the magazines of that day usually enjoyed only an ephemeral life-span. After two years of fatiguing effort to breathe life into periodicals, he became Assistant Editor of the New-York Evening Post under William Coleman, a newspaper founded by Alexander Hamilton that was surviving precariously. Within two years, he was Editor-in-Chief and a part owner. He remained the Editor-in-Chief for half a century (1828–78). Eventually, the Evening-Post became not only the foundation of his fortune but also the means by which he exercised considerable political power in his city, state, and nation. Ironically, the boy who first tasted fame for his diatribe against Thomas Jefferson and his party became one of the key supporters in the Northeast of that same party under Jackson. Bryant's views, always progressive though not quite populist, in course led him to join the Free Soilers, and when the Free Soil Party became a core of the new Republican Party in 1856, Bryant vigorously campaigned for John Frémont. That exertion enhanced his standing in party councils, and in 1860, he was one of the prime Eastern exponents of Abraham Lincoln, whom he introduced at Cooper Union. (That "Cooper Union speech" lifted Lincoln to the nomination, and then the presidency.) Bryant edited the very successful Picturesque America which was published between 1872 and 1874. This two-volume set was lavishly illustrated and described scenic places in the United States and Canada. Later Years In his last decade, Bryant shifted from writing his own poetry to translating Homer. He assiduously worked on the Iliad and The Odyssey from 1871 to 1874. He is also remembered as one of the principal authorities on homeopathy and as a hymnist for the Unitarian Church—both legacies of his father's enormous influence on him. Bryant died in 1878 of complications from an accidental fall suffered after participating in a Central Park ceremony honoring Italian patriot Giuseppe Mazzini.)

The Best Poem Of William Cullen Bryant

Thanatopsis

To him who in the love of nature holds

Communion with her visible forms, she speaks

A various language; for his gayer hours

She has a voice of gladness, and a smile

And eloquence of beauty; and she glides

Into his darker musings, with a mild

And healing sympathy that steals away

Their sharpness ere he is aware. When thoughts

Of the last bitter hour come like a blight

Over thy spirit, and sad images

Of the stern agony, and shroud, and pall,

And breathless darkness, and the narrow house,

Make thee to shudder, and grow sick at heart;--

Go forth, under the open sky, and list

To Nature's teachings, while from all around--

Earth and her waters, and the depths of air--

Comes a still voice. Yet a few days, and thee

The all-beholding sun shall see no more

In all his course; nor yet in the cold ground,

Where thy pale form was laid, with many tears,

Nor in the embrace of ocean, shall exist

Thy image. Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim

Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again,

And, lost each human trace, surrendering up

Thine individual being, shalt thou go

To mix forever with the elements,

To be a brother to the insensible rock

And to the sluggish clod, which the rude swain

Turns with his share, and treads upon. The oak

Shall send his roots abroad, and pierce thy mold.

Yet not to thine eternal resting-place

Shalt thou retire alone, nor couldst thou wish

Couch more magnificent. Thou shalt lie down

With patriarchs of the infant world -- with kings,

The powerful of the earth -- the wise, the good,

Fair forms, and hoary seers of ages past,

All in one mighty sepulchre. The hills

Rock-ribbed and ancient as the sun, -- the vales

Stretching in pensive quietness between;

The venerable woods -- rivers that move

In majesty, and the complaining brooks

That make the meadows green; and, poured round all,

Old Ocean's gray and melancholy waste,--

Are but the solemn decorations all

Of the great tomb of man. The golden sun,

The planets, all the infinite host of heaven,

Are shining on the sad abodes of death

Through the still lapse of ages. All that tread

The globe are but a handful to the tribes

That slumber in its bosom. -- Take the wings

Of morning, pierce the Barcan wilderness,

Or lose thyself in the continuous woods

Where rolls the Oregon, and hears no sound,

Save his own dashings -- yet the dead are there:

And millions in those solitudes, since first

The flight of years began, have laid them down

In their last sleep -- the dead reign there alone.

So shalt thou rest -- and what if thou withdraw

In silence from the living, and no friend

Take note of thy departure? All that breathe

Will share thy destiny. The gay will laugh

When thou art gone, the solemn brood of care

Plod on, and each one as before will chase

His favorite phantom; yet all these shall leave

Their mirth and their employments, and shall come

And make their bed with thee. As the long train

Of ages glides away, the sons of men--

The youth in life's fresh spring, and he who goes

In the full strength of years, matron and maid,

The speechless babe, and the gray-headed man--

Shall one by one be gathered to thy side,

By those, who in their turn, shall follow them.

So live, that when thy summons comes to join

The innumerable caravan, which moves

To that mysterious realm, where each shall take

His chamber in the silent halls of death,

Thou go not, like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon, but, sustained and soothed

By an unfaltering trust, approach thy grave

Like one who wraps the drapery of his couch

About him, and lies down to pleasant dreams.

William Cullen Bryant Comments

tell me not a mournful number, life is but a empty dream, for the soul is dead that slumbers and life is not what it seems

William Cullen Bryant Quotes

Difficulty, my brethren, is the nurse of greatness—a harsh nurse, who roughly rocks her foster-children into strength and athletic proportion.

It is a creole asking