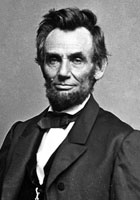

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln Poems

I

My childhood's home I see again,

And sadden with the view;

...

You are young, and I am older;

You are hopeful, I am not -

Enjoy life, ere it grow colder -

Pluck the roses ere they rot.

...

Here, where the lonely hooting owl

Sends forth his midnight moans,

Fierce wolves shall o’er my carcase growl,

Or buzzards pick my bones.

...

A wild-bear chace, didst never see?

Then hast thou lived in vain.

Thy richest bump of glorious glee,

Lies desert in thy brain.

...

Abraham Lincoln is my nam[e]

And with my pen I wrote the same

I wrote in both hast and speed

and left it here for fools to read

...

MY childhood's home I see again,

And sadden with the view;

And still, as memory crowds my brain,

There's pleasure in it, too.

...

Abraham Lincoln,

His hand and pen:

He will be good but

God knows When.

...

A sweet plaintive song did I hear,

And I fancied that she was the singer—

May emotions as pure, as that song set a-stir

...

Gen. Lees invasion of the North written by himself—

In eighteen sixty three, with pomp,

and mighty swell,

...

Abraham Lincoln Biography

Abraham Lincoln was the 16th President of the United States, serving from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. He successfully led his country through a great constitutional, military and moral crisis – the American Civil War – preserving the Union, while ending slavery, and promoting economic and financial modernization. Reared in a poor family on the western frontier, Lincoln was mostly self-educated. He became a country lawyer, an Illinois state legislator, and a one-term member of the United States House of Representatives, but failed in two attempts to be elected to the United States Senate. After opposing the expansion of slavery in the United States in his campaign debates and speeches, Lincoln secured the Republican nomination and was elected president in 1860. Before Lincoln took office in March, seven southern slave states declared their secession and formed the Confederacy. When war began with the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, Lincoln concentrated on both the military and political dimensions of the war effort, seeking to reunify the nation. He vigorously exercised unprecedented war powers, including the arrest and detention without trial of thousands of suspected secessionists. He prevented British recognition of the Confederacy by skillfully handling the Trent affair late in 1861. He issued his Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and promoted the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, abolishing slavery. Lincoln closely supervised the war effort, especially the selection of top generals, including commanding general Ulysses S. Grant. He brought leaders of various factions of his party into his cabinet and pressured them to cooperate. Under his leadership, the Union set up a naval blockade that shut down the South's normal trade, took control of the border slave states at the start of the war, gained control communications with gunboats on the southern river systems, and tried repeatedly to capture the Confederate capital at Richmond. Each time a general failed, Lincoln substituted another until finally Grant succeeded in 1865. An exceptionally astute politician deeply involved with power issues in each state, he reached out to War Democrats and managed his own re-election in the 1864 presidential election. As the leader of the moderate faction of the Republican party, Lincoln found his policies and personality were "blasted from all sides": Radical Republicans demanded harsher treatment of the South, War Democrats desired more compromise, Copperheads despised him, and irreconcilable secessionists plotted his death. Politically, Lincoln fought back with patronage, by pitting his opponents against each other, and by appealing to the American people with his powers of oratory.His Gettysburg Address of 1863 became the most quoted speech in American history. It was an iconic statement of America's dedication to the principles of nationalism, equal rights, liberty, and democracy. At the close of the war, Lincoln held a moderate view of Reconstruction, seeking to speedily reunite the nation through a policy of generous reconciliation in the face of lingering and bitter divisiveness. But six days after the surrender of Confederate commanding general Robert E. Lee, Lincoln was assassinated by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth at Ford's Theatre. His death was the first assassination of a U.S. president and sent the northern parts of the country into mourning. Lincoln has been consistently ranked by scholars and the public as one of the three greatest U.S. presidents Poetry Throughout his life, Abraham Lincoln was an avid reader of poetry. As a teenager, however, Lincoln also began to cultivate an interest in writing poetry. Lincoln's oldest surviving verses, written when he was between fifteen and seventeen years old, are brief squibs that appear in his arithmetic book. During his teens and early twenties, Lincoln wrote a number of crude and satirical verses. The poem that Lincoln's neighbors best remembered from this period was the "Chronicles of Reuben," which his neighbor, Joseph C. Richardson, claimed was "remembered here in Indiana in scraps better than the Bible." The history behind the poem reveals that, when provoked, Lincoln could wield his pen as a blunt instrument of attack. In 1826, Lincoln's sister Sarah married Aaron Grigsby, whose family were neighbors of the Lincolns. When Sarah died in childbirth in 1828, Lincoln blamed Aaron and the Grigsbys for delaying to call a doctor. The incident created a rift between Lincoln and the Grigsbys. Lincoln's bitterness increased when he was not invited to the joint wedding celebration of Aaron's brothers Reuben and Charles, who married on the same day. In revenge, Lincoln appears to have arranged, through a friend, for Reuben and Charles to be brought to the wrong bedrooms, where each other's new wives awaited after the wedding party. Lincoln then wrote a description of the incident known as the "Chronicles of Reuben" as payback. Patterned after biblical scripture, the prose narrative was followed by a poem about Billy Grigsby, another of Aaron's brothers. The coarse poem ridicules the failed attempts of Billy to woo girls. The original text of the "The Chronicles of Reuben" does not survive, though several of Lincoln's neighbor's later recollected the poem for William Herndon. One of Lincoln's Springfield neighbors, James Matheny, recalled that sometime between 1837-39 Lincoln joined "a Kind of Poetical Society" to which he occasionally submitted poems. Although none of the poems survive, Matheny remembered one eye-raising stanza from a poem "on Seduction": Whatever Spiteful fools may Say — Each jealous, ranting yelper — No woman ever played the whore Unless She had a man to help her. Lincoln wrote his most serious poetry in 1846. The limited information that exists about their composition comes from comes from Lincoln's correspondence with Andrew Johnston, a fellow lawyer and Whig politician from Quincy, Illinois. In a letter to Johnston on February 24, 1846, Lincoln wrote: Feeling a little poetic this evening, I have concluded to redeem my promise this evening by sending you the piece you expressed the wish to have. You find it enclosed. I wish I could think of something else to say; but I believe I can not. By the way, would you like to see a piece of poetry of my own making? I have a piece that is almost done, but I find a deal of trouble to finish it. The poem Lincoln alluded to is "My Childhood-Home I See Again." It was completed shortly after Lincoln's message to Johnston When Lincoln later edited the poem, he divided it into two sections, or cantos. He sent the first canto to Johnston in an April 18, 1846 letter, noting that it was intended to be the first section of a larger poem he was working on. In the letter, Lincoln preceded the text of the canto by describing the circumstances that led him to write it: In the fall of 1844, thinking I might aid some to carry the State of Indiana for Mr. Clay, I went into the neighborhood in that State in which I was raised, where my mother and sister were buried, and from which I had been absent about fifteen years. That part of the country is, within itself, as unpoetical as any spot of the earth; but still, seeing it and its objects and inhabitants aroused feelings in me which were certainly poetry; though whether my expression of those feelings is poetry is quite another question. When I got to writing, the change of subjects divided the think into four little divisions or cantos, the first only of which I send you now and may send the others hereafter. Lincoln sent the second canto to Johnston in his letter of September 6, 1846. Lincoln introduced the canto to Johnston in the following manner: You remember when I wrote you from Tremont last spring, sending you a little canto of what I called poetry, I promised to bore you with another some time. I now fulfil the promise. The subject of the present one is an insane man. His name is Matthew Gentry. He is three years older than I, and when we were boys we went to school together. He was rather a bright lad, and the son of the rich man of our very poor neighbourhood. At the age of nineteen he unaccountably became furiously mad, from which condition he gradually settled down into harmless insanity. When, as I told you in my other letter I visited my old home in the fall of 1844, I found him still lingering in this wretched condition. In my poetizing mood I could not forget the impression his case made upon me. Transcriptions of both cantos (under the title "My Childhood's Home I See Again") as they appeared in Lincoln's letters to Johnston can be read online through the Representative Poetry Online web site. At the end of Lincoln's September 6 letter, he told Johnston that "if I should ever send another [poem], the subject will be a "Bear Hunt." In the next letter that Lincoln sent Johnston (February 25, 1847) Lincoln did in fact send Johnston another poem. Replying to Johnston's offer to publish the first two cantos of his poems, Lincoln wrote: "To say the least, I am not at all displeased with your proposal to publish the poetry, or doggerel, or whatever else it may be called, which I sent you. I consent that it may be done, together which the third canto, which I now send you." It is probable that the third canto Lincoln sent to Johnston was "The Bear Hunt." Lincoln continued to compose poems in subsequent years, though none as substantial as those written in 1846. On September 28, 1858, Lincoln wrote the following verses "in the autograph album of Rosa Haggard, daughter of the proprietor of the hotel at Winchester, Illinois, where he stayed when speaking at that place on the same date": To Rosa— You are young, and I am older; You are hopeful, I am not— Enjoy life, ere it grow colder— Pluck the roses ere they rot. Teach your beau to heed the lay— That sunshine soon is lost in shade— That now's as good as any day— To take thee, Rose, ere she fade. Similarly, on September 30, 1858, Lincoln wrote the following verse to Rosa's sister Linnie Haggard: To Linnie— A sweet plaintive song did I hear, And I fancied that she was the singer— May emotions as pure, as that song set a-stir Be the worst that the future shall bring her. Lincoln's last documented verse was written July 19, 1863, in response to the North's victory in the Battle of Gettysburg: Verse on Lee's Invasion of the North Gen. Lees invasion of the North written by himself— In eighteen sixty three, with pomp, and mighty swell, Me and Jeff's Confederacy, went forth to sack Phil-del, The Yankees they got arter us, and giv us particular hell, And we skedaddled back again, And didn't sack Phil-del. In 2004, news broke that a poem entitled "The Suicide's Soliloquy," published in the August 25, 1838, issue of the Sangamo Journal, may have been written by Lincoln. While many scholars believe that Lincoln is indeed the author of the poem, there is no consensus. The announcement of the poem's possible author first appeared in the 2004 Spring newsletter of the Abraham Lincoln Association. The text of the poem, along with the introduction that precedes it in the Sangamo Journal, follows below. THE SUICIDE'S SOLILOQUY. The following lines were said to have been found near the bones of a man supposed to have committed suicide, in a deep forest, on the Flat Branch of the Sangamon, some time ago. Here, where the lonely hooting owl Sends forth his midnight moans, Fierce wolves shall o'er my carcase growl, Or buzzards pick my bones. No fellow-man shall learn my fate, Or where my ashes lie; Unless by beasts drawn round their bait, Or by the ravens' cry. Yes! I've resolved the deed to do, And this the place to do it: This heart I'll rush a dagger through, Though I in hell should rue it! Hell! What is hell to one like me Who pleasures never know; By friends consigned to misery, By hope deserted too? To ease me of this power to think, That through my bosom raves, I'll headlong leap from hell's high brink, And wallow in its waves. Though devils yell, and burning chains May waken long regret; Their frightful screams, and piercing pains, Will help me to forget. Yes! I'm prepared, through endless night, To take that fiery berth! Think not with tales of hell to fright Me, who am damn'd on earth! Sweet steel! come forth from out your sheath, And glist'ning, speak your powers; Rip up the organs of my breath, And draw my blood in showers! I strike! It quivers in that heart Which drives me to this end; I draw and kiss the bloody dart, My last—my only friend!)

The Best Poem Of Abraham Lincoln

My Childhood Home I See Again

I

My childhood's home I see again,

And sadden with the view;

And still, as memory crowds my brain,

There's pleasure in it too.

O Memory! thou midway world

'Twixt earth and paradise,

Where things decayed and loved ones lost

In dreamy shadows rise,

And, freed from all that's earthly vile,

Seem hallowed, pure, and bright,

Like scenes in some enchanted isle

All bathed in liquid light.

As dusky mountains please the eye

When twilight chases day;

As bugle-tones that, passing by,

In distance die away;

As leaving some grand waterfall,

We, lingering, list its roar--

So memory will hallow all

We've known, but know no more.

Near twenty years have passed away

Since here I bid farewell

To woods and fields, and scenes of play,

And playmates loved so well.

Where many were, but few remain

Of old familiar things;

But seeing them, to mind again

The lost and absent brings.

The friends I left that parting day,

How changed, as time has sped!

Young childhood grown, strong manhood gray,

And half of all are dead.

I hear the loved survivors tell

How nought from death could save,

Till every sound appears a knell,

And every spot a grave.

I range the fields with pensive tread,

And pace the hollow rooms,

And feel (companion of the dead)

I'm living in the tombs.

II

But here's an object more of dread

Than ought the grave contains--

A human form with reason fled,

While wretched life remains.

Poor Matthew! Once of genius bright,

A fortune-favored child--

Now locked for aye, in mental night,

A haggard mad-man wild.

Poor Matthew! I have ne'er forgot,

When first, with maddened will,

Yourself you maimed, your father fought,

And mother strove to kill;

When terror spread, and neighbors ran,

Your dange'rous strength to bind;

And soon, a howling crazy man

Your limbs were fast confined.

How then you strove and shrieked aloud,

Your bones and sinews bared;

And fiendish on the gazing crowd,

With burning eye-balls glared--

And begged, and swore, and wept and prayed

With maniac laught[ter?] joined--

How fearful were those signs displayed

By pangs that killed thy mind!

And when at length, tho' drear and long,

Time smoothed thy fiercer woes,

How plaintively thy mournful song

Upon the still night rose.

I've heard it oft, as if I dreamed,

Far distant, sweet, and lone--

The funeral dirge, it ever seemed

Of reason dead and gone.

To drink it's strains, I've stole away,

All stealthily and still,

Ere yet the rising God of day

Had streaked the Eastern hill.

Air held his breath; trees, with the spell,

Seemed sorrowing angels round,

Whose swelling tears in dew-drops fell

Upon the listening ground.

But this is past; and nought remains,

That raised thee o'er the brute.

Thy piercing shrieks, and soothing strains,

Are like, forever mute.

Now fare thee well--more thou the cause,

Than subject now of woe.

All mental pangs, by time's kind laws,

Hast lost the power to know.

O death! Thou awe-inspiring prince,

That keepst the world in fear;

Why dost thos tear more blest ones hence,

And leave him ling'ring here?

Abraham Lincoln Comments

It would cool to find out if he did live from the assassination. They would keep it a secret. That would be cool.

All of you have terrible grammar. You should look in a dictionary sometime.

if you do not anything nice to say. then don't say anything at all.

I loved this person as unforgettable world leader and after reading his poems I love also him as true poet of the world.

Abraham Lincoln Quotes

We cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract.

Our government rests in public opinion. Whoever can change public opinion, can change the government, practically just so much.

The true rule, in determining to embrace, or reject any thing, is not whether it have any evil in it; but whether it have more of evil, than of good. There are few things wholly evil, or wholly good.

And then, the negro being doomed, and damned, and forgotten, to everlasting bondage, is the white man quite certain that the tyrant demon will not turn upon him too?

Holding myself the humblest of all whose names were before the convention, I feel in especial need of the assistance of all.

I wish to see, in process of disappearing, that only thing which ever could bring this nation to civil war.

I never did ask more, nor ever was willing to accept less, than for all the States, and the people thereof, to take and hold their places, and their rights, in the Union, under the Constitution of the United States. For this alone have I felt authorized to struggle; and I seek neither more nor less now.

In the present civil war it is quite possible that God's purpose is something different from the purpose of either party.

What is conservatism? Is it not adherence to the old and tried, against the new and untried?

I am in no boastful mood. I shall not do more than I can, and I shall do all I can to save the government, which is my sworn duty as well as my personal inclination. I shall do nothing in malice. What I deal with is too vast for malicious dealing.

Fellow-citizens, we cannot escape history.

If you would win a man to your cause, first convince him that you are his sincere friend. Therein is a drop of honey that catches his heart, which, say what you will, is the great high-road to his reason, and which, when once gained, you will find but little trouble in convincing his judgment of the justice of your cause.

So long as I have been here I have not willingly planted a thorn in any man's bosom.

The ballot is stronger than the bullet.

I never knew a man who wished to be himself a slave. Consider if you know any good thing, that no man desires for himself.

Fair play is a jewell [sic]. Give him a chance if you can.

Every man is said to have his peculiar ambition. Whether it be true or not, I can say for one that I have no other so great as that of being truly esteemed of my fellow men....

I hold the value of life is to improve one's condition. Whatever is calculated to advance the condition of the honest, struggling laboring man, so far as my judgment will enable me to judge of a correct thing, I am for that thing.

If I fail, it will be for lack of ability, and not of purpose.

A right result, at this time, will be worth more to the world, than ten times the men, and ten times the money.

My father, at the death of his father, was but six years of age; and he grew up, literally without education.

Our down East friends, did, indeed, treat me with great kindness, demonstrating what I before believed, that all good, intelligent people are very much alike.

If there is ANY THING which it is the duty of the WHOLE PEOPLE to never entrust to any hands but their own, that thing is the preservation and perpetuity, of their own liberties, and institutions.

You have constantly urged the idea that you were persecuted because you did not come from West-Point, and you repeat it in these letters. This, my dear general, is I fear, the rock on which you have split.

Remembering that when not a very great man begins to be mentioned for a very great position, his head is very likely to be a little turned, I concluded I am not the fittest person to answer the questions you ask.

I go for all sharing the privileges of the government, who assist in bearing its burthens.

It has long been a grave question whether any government, not too strong for the liberties of its people, can be strong enough to maintain its own existence, in great emergencies.

The matter of fees is important, far beyond the mere question of bread and butter involved. Properly attended to, fuller justice is done to both lawyer and client.

Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith, let us, to the end, dare to do our duty as we understand it.

In the hope that it may be no intrusion upon the sacredness of your sorrow, I have ventured to address you this tribute to the memory of my young friend, and your brave and early fallen child. May God give you that consolation which is beyond all earthly power.

Gen. Schurz thinks I was a little cross in my late note to you. If I was, I ask pardon. If I do get up a little temper I have no sufficient time to keep it up.

I ... ran for Legislature [in 1832] ... and was beaten—the only time I have been beaten by the people.

If the union of these States, and the liberties of this people, shall be lost, it is but little to any one man of fifty-two years of age, but a great deal to the thirty millions of people who inhabit these United States, and to their posterity in all coming time.

[With the Union saved] its form of government is saved to the world; its beloved history, and cherished memories, are vindicated; and its happy future fully assured, and rendered inconceivably grand.

We want, and must have, a national policy, as to slavery, which deals with it as being wrong.

You may have a wen or a cancer upon your person and not be able to cut it out lest you bleed to death; but surely it is no way to cure it, to engraft it and spread it over your whole body.

I have just read your dispatch about sore tongued and fatiegued [sic] horses. Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietem that fatigue anything?

We find ourselves under the government of a system of political institutions, conducing more essentially to the ends of civil and religious liberty, than any of which the history of former times tells us.

When I came of age I did not know much. Still somehow, I could read, write, and cipher to the Rule of Three.... The little advance I now have upon this store of education, I have picked up from time to time under the pressure of necessity.

Every head should be cultivated.

I have heard, in such a way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command. Only those generals who gain success, can set up dictators.

The people will save their government, if the government itself will allow them.

The fiery trial through which we pass, will light us down, in honor or dishonor, to the latest generation.

In this sad world of ours, sorrow comes to all; and, to the young, it comes with bitterest agony, because it takes them unawares. The older have learned to ever expect it.

Allow me to assure you, that suspicion and jealousy never did help any man in any situation.

I was losing interest in politics, when the repeal of the Missouri Compromise aroused me again. What I have done since then is pretty well known.

Beware of rashness. Beware of rashness, but with energy, and sleepless vigilance, go forward, and give us victories.

These men ask for just the same thing—fairness, and fairness only. This, so far as in my power, they, and all others, shall have.

The people themselves, and not their servants, can safely reverse their own deliberate decisions.

I have always thought that all men should be free; but if any should be slaves it should be first those who desire it for themselves, and secondly those who desire it for others. Whenever [I] hear anyone, arguing for slavery I feel a strong impulse to see it tried on him personally.

Abraham Lincoln is one of my favorite presedint in the world! ! : D