Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Brooks Poems

Abortions will not let you forget.

You remember the children you got that you did not get,

The damp small pulps with a little or with no hair,

The singers and workers that never handled the air.

...

I shall not sing a May song.

A May song should be gay.

I'll wait until November

And sing a song of gray.

...

To be in love

Is to touch with a lighter hand.

In yourself you stretch, you are well.

You look at things

...

Maud went to college.

Sadie stayed home.

Sadie scraped life

With a fine toothed comb.

...

Oh mother, mother, where is happiness?

They took my lover's tallness off to war,

Left me lamenting. Now I cannot guess

What I can use an empty heart-cup for.

...

Say to them,

say to the down-keepers,

the sun-slappers,

the self-soilers,

...

I hold my honey and I store my bread

In little jars and cabinets of my will.

I label clearly, and each latch and lid

I bid, Be firm till I return from hell.

...

Already I am no longer looked at with lechery or love.

My daughters and sons have put me away with marbles and dolls,

Are gone from the house.

My husband and lovers are pleasant or somewhat polite

...

They eat beans mostly, this old yellow pair.

Dinner is a casual affair.

Plain chipware on a plain and creaking wood,

Tin flatware.

...

Rudolph Reed was oaken.

His wife was oaken too.

And his two good girls and his good little man

Oakened as they grew.

...

We are things of dry hours and the involuntary plan,

Grayed in, and gray. "Dream" mate, a giddy sound, not strong

Like "rent", "feeding a wife", "satisfying a man".

...

From the first it had been like a

Ballad. It had the beat inevitable. It had the blood.

A wildness cut up, and tied in little bunches,

Like the four-line stanzas of the ballads she had never quite

...

What do you think of us in fuzzy endeavor, you whose directions are

sterling, whose lunge is straight?

...

The good man.

He is still enhancer, renouncer.

In the time of detachment,

in the time of the vivid heather and affectionate evil,

...

you did not know you were Afrika

When you set out for Afrika

you did not know you were going.

...

arrive. The Ladies from the Ladies' Betterment League

Arrive in the afternoon, the late light slanting

In diluted gold bars across the boulevard brag

Of proud, seamed faces with mercy and murder hinting

...

Now who could take you off to tiny life

In one room or in two rooms or in three

And cork you smartly, like the flask of wine

You are? Not any woman. Not a wife.

...

I’ve stayed in the front yard all my life.

I want a peek at the back

Where it’s rough and untended and hungry weed grows.

A girl gets sick of a rose.

...

There is a little lightning in his eyes.

Iron at the mouth.

His brows ride neither too far up nor down.

He is splendid. With a place to stand.

...

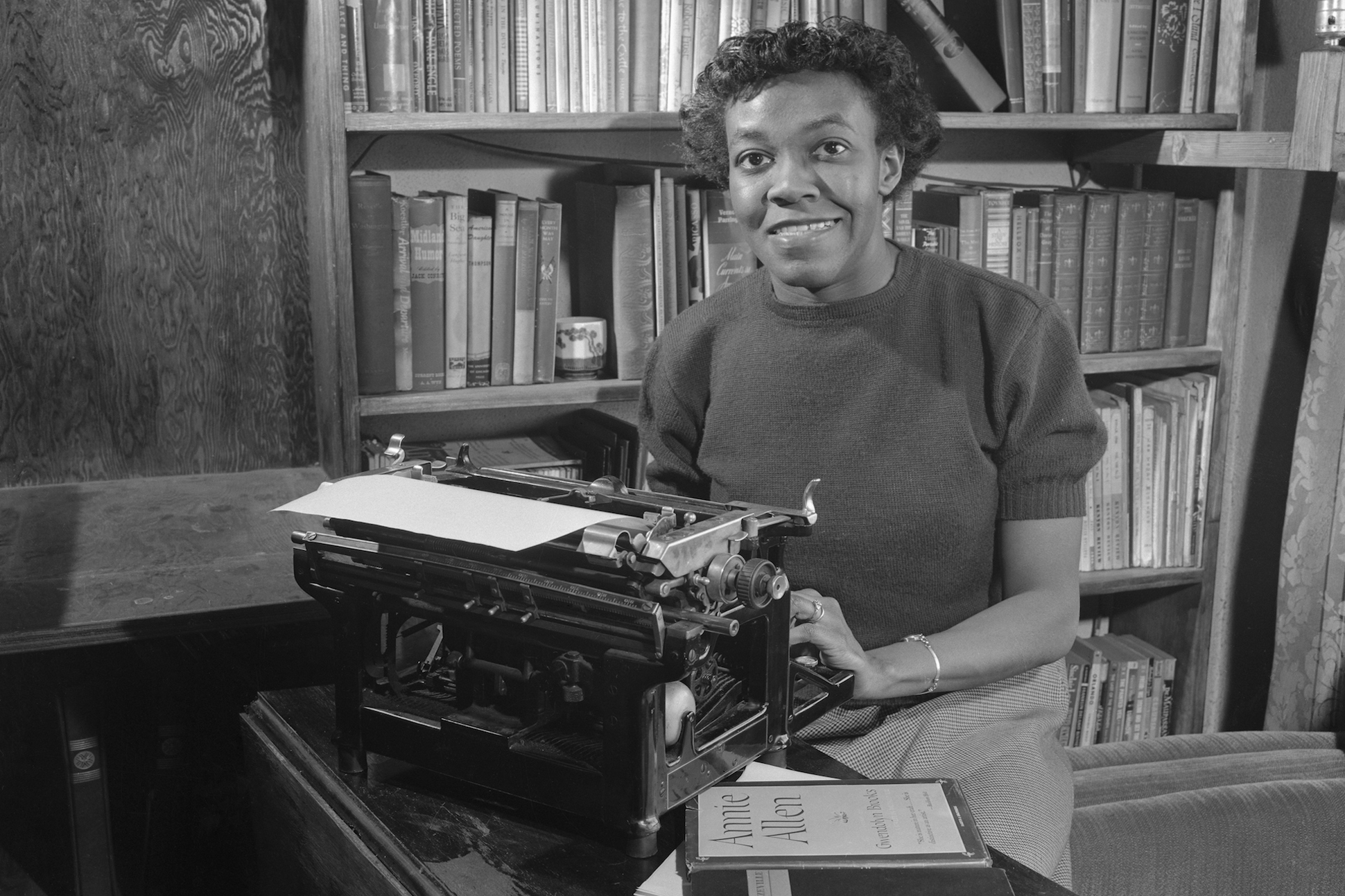

Gwendolyn Brooks Biography

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks was an African-American poet. She was appointed Poet Laureate of Illinois in 1968 and Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress in 1985. Biography Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks was born on June 7, 1917, in Topeka, Kansas, the first child of David Anderson Brooks and Keziah Wims. Her mother was a former school teacher who had chosen that field because she could not afford to attend medical school. (Family lore held that her paternal grandfather had escaped slavery to join Union forces during the American Civil War.) When Brooks was six weeks old, her family moved to Chicago, Illinois during the Great Migration; from then on, Chicago was her hometown. She went by the nickname "Gwendie" among her close friends. Her home life was stable and loving, although she encountered racial prejudice in her neighborhood and in schools. She attended Hyde Park High School, the leading white high school in the city, before transferring to the all-black Wendell Phillips. Brooks eventually attended an integrated school, Englewood High School. In 1936 she graduated from Wilson Junior College. These four schools gave her a perspective on racial dynamics in the city that continued to influence her work. Career Brooks published her first poem in a children's magazine at the age of thirteen. By the time she was sixteen, she had compiled a portfolio of around 75 published poems. At seventeen, she started submitting her work to "Lights and Shadows", the poetry column of the Chicago Defender, an African-American newspaper. Her poems, many published while she attended Wilson Junior College, ranged in style from traditional ballads and sonnets to poems using blues rhythms in free verse. Her characters were often drawn from the poor of the inner city. After failing to obtain a position with the Chicago Defender, Brooks took a series of secretarial jobs. By 1941, Brooks was taking part in poetry workshops. A particularly influential one was organized by Inez Cunningham Stark, an affluent white woman with a strong literary background. The group dynamic of Stark's workshop, all of whose participants were African American, energized Brooks. Her poetry began to be taken seriously. In 1943 she received an award for poetry from the Midwestern Writers' Conference. Brooks' first book of poetry, A Street in Bronzeville (1945), published by Harper and Row, earned instant critical acclaim. She received her first Guggenheim Fellowship and was included as one of the “Ten Young Women of the Year” in Mademoiselle magazine. With her second book of poetry, Annie Allen (1950), she became the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize for poetry; she also was awarded Poetry magazine’s Eunice Tietjens Prize. After President John F. Kennedy invited Brooks to read at a Library of Congress poetry festival in 1962, she began a second career teaching creative writing. She taught at Columbia College Chicago, Northeastern Illinois University, Chicago State University, Elmhurst College, Columbia University, Clay College of New York, and the University of Wisconsin–Madison. In 1967 she attended a writers’ conference at Fisk University where, she said, she rediscovered her blackness. This rediscovery is reflected in her work In The Mecca (1968), a long poem about a mother searching for her lost child in a Chicago apartment building. In The Mecca was nominated for the National Book Award for poetry. On May 1, 1996 Brooks returned to her birthplace of Topeka, Kansas. She was invited as the keynote speaker for the Third Annual Kaw Valley Girl Scout Council's "Women of Distinction Banquet and String of Pearls Auction." A ceremony was held in her honor at a local park at 37th and Topeka Boulevard. Personal In 1939 Brooks married Henry Lowington Blakely, Jr. They had two children: Henry Lowington Blakely III, born October 10, 1940; and Nora Blakely, born in 1951. From mid-1961 to late-1964, Henry III served in the U.S. Marine Corps, first at Marine Corps Recruit Depot San Diego and then at Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay. During this time, Brooks mentored his fiancee, Kathleen Hardiman, today known as anthropologist Kathleen Rand Reed, in writing poetry. Upon his return, Blakely and Hardiman married in 1965. Brooks had so enjoyed the mentoring relationship that she began to engage more frequently in that role with the new generation of young black poets. Legacy and Honors 1968, appointed Poet Laureate of Illinois. 1985, selected as the Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, an honorary one-year position whose title changed the next year to Poet Laureate. 1988, inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. 1994, chosen as the National Endowment for the Humanities' Jefferson Lecturer, one of the highest honors in American literature and the highest award in the humanities given by the federal government. 1995, presented with the National Medal of Arts. 1995, honored as the first Woman of the Year chosen by the Harvard Black Men's Forum. Other awards she received included the Frost Medal, the Shelley Memorial Award, and an award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Brooks also received more than seventy-five honorary degrees from colleges and universities worldwide. Brooks died at age 83 on December 3, 2000, at her Southside Chicago home. She is buried at Lincoln Cemetery in Blue Island, Illinois.)

The Best Poem Of Gwendolyn Brooks

We Real Cool

The Pool Players.

Seven at the Golden Shovel.

We real cool. We

Left school. We

Lurk late. We

Strike straight. We

Sing sin. We

Thin gin. We

Jazz June. We

Die soon.

Gwendolyn Brooks Comments

'Sadie and Maud' by Gwendolyn Brooks is one of the poems that I think women all around the world should have the pleasure of reading. It signifies the independent lives that women have and the joy that life might bring.

I don't even like poems but she's really swaggy and fresh

No Experience Needed, No Boss Over il Your FD Shoulder… Say Goodbye To Your Old Job! Predetermined Number Of Spots Openit........ fuljobz.com

Can someone post the full poem called 'to those of my sisters who kept their naturals'? ! ? ! ? ! Thank you! !

Gwendolyn Brooks ranked #46 on top 500 poets on date 16 December 2020 has written many wonderful poems which motivate many readers of the world.

THE U.S. POET LAUREATE IN 1985, SAID THAT" POETRY IS LIFE DISTILLED." THIS IS AN EXAMPLE OF A/AN A.SIMILE B.METAPHOR C.ALLEGORY D.PERSONIFICATION

Gwendolyn Brooks Quotes

I don't like the idea of the black race being diluted out of existence. I like the idea of all of us being here.

Gwendolyn Brooks has written some very nice poems.