Countee Cullen

Countee Cullen Poems

Once riding in old Baltimore,

Heart-filled, head-filled with glee,

I saw a Baltimorean

Keep looking straight at me.

...

With two white roses on her breasts,

White candles at head and feet,

Dark Madonna of the grave she rests;

Lord Death has found her sweet.

...

All through an empty place I go,

And find her not in any room;

The candles and the lamps I light

Go down before a wind of gloom.

...

What is Africa to me:

Copper sun or scarlet sea,

Jungle star or jungle track,

Strong bronzed men, or regal black

...

My father is a quiet man

With sober, steady ways;

For simile, a folded fan;

His nights are like his days.

...

Dead men are wisest, for they know

How far the roots of flowers go,

How long a seed must rot to grow.

...

We shall not always plant while others reap

The golden increment of bursting fruit,

Not always countenance, abject and mute,

That lesser men should hold their brothers cheap;

...

"Lord, being dark," I said, "I cannot bear

The further touch of earth, the scented air;

Lord, being dark, forewilled to that despair

My color shrouds me in, I am as dirt

...

Then call me traitor if you must,

Shout reason and default!

Say I betray a sacred trust

Aching beyond this vault.

...

I have wrapped my dreams in a silken cloth,

And laid them away in a box of gold;

Where long will cling the lips of the moth,

I have wrapped my dreams in a silken cloth;

...

He never spoke a word to me,

And yet He called my name;

He never gave a sign to me,

And yet I knew and came.

...

Some are teethed on a silver spoon,

With the stars strung for a rattle;

I cut my teeth as the black racoon--

For implements of battle.

...

She even thinks that up in heaven

Her class lies late and snores

While poor black cherubs rise at seven

...

I doubt not God is good, well-meaning, kind

And did He stoop to quibble could tell why

The little buried mole continues blind,

Why flesh that mirrors Him must some day die,

...

The many sow, but only the chosen reap;

Happy the wretched host if Day be brief,

...

That bright chimeric beast

Conceived yet never born,

Save in the poet's breast,

The white-flanked unicorn,

...

This is not water running here,

These thick rebellious streams

That hurtle flesh and bone past fear

Down alleyways of dreams

...

Locked arm in arm they cross the way

The black boy and the white,

The golden splendor of the day

The sable pride of night.

...

I have a rendezvous with Life,

In days I hope will come,

Ere youth has sped, and strength of mind,

Ere voices sweet grow dumb.

...

I cannot hold my peace, John Keats;

There never was a spring like this;

It is an echo, that repeats

...

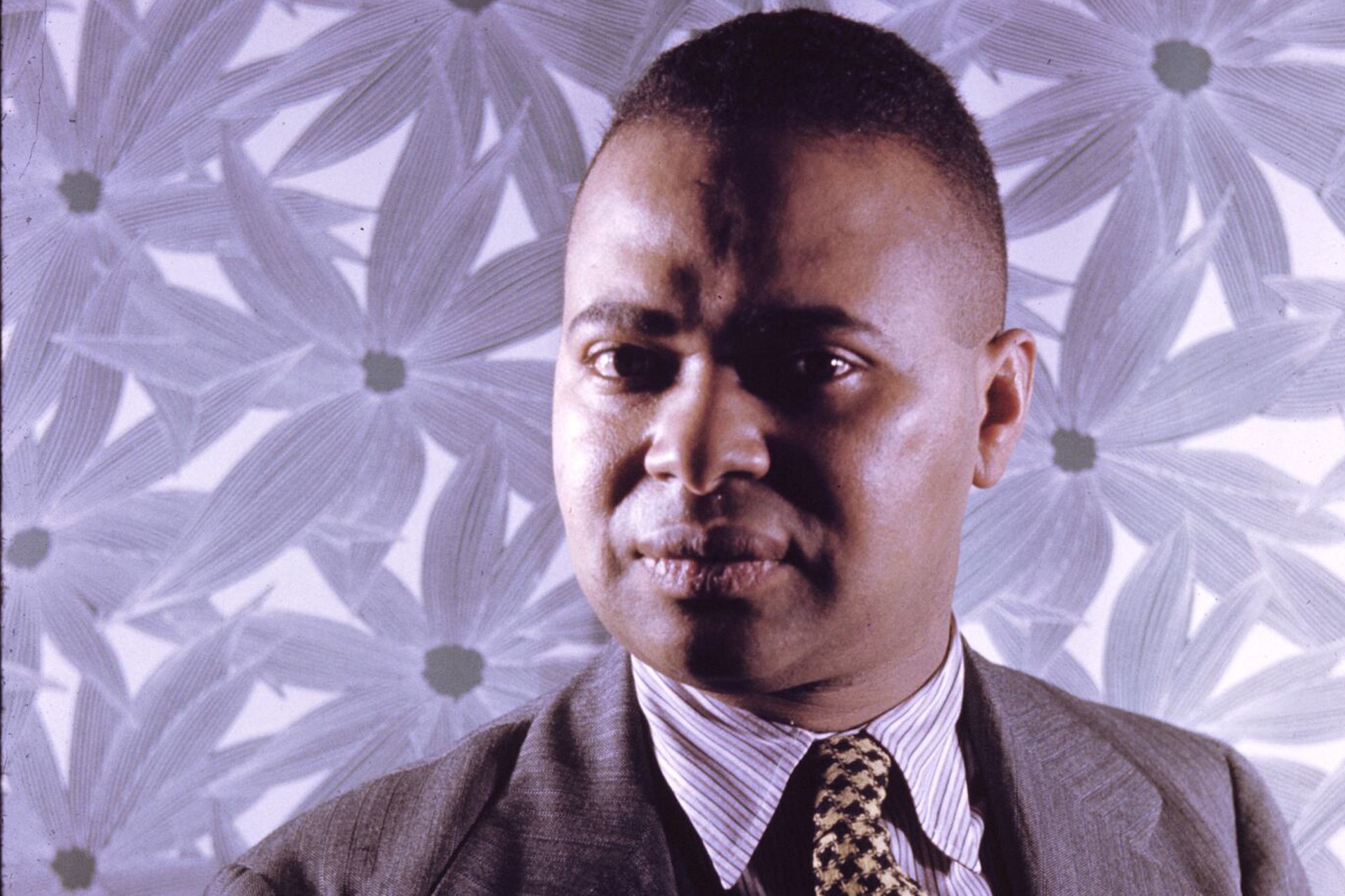

Countee Cullen Biography

Countee Cullen was an American poet who was a leading figure in the Harlem Renaissance. Early life Countee Cullen was possibly born on May 30, although due to conflicting accounts of his early life, a general application of the year of his birth as 1903 is reasonable. He was either born in New York, Baltimore, or Lexington, Kentucky, with his widow being convinced he was born in Lexington. Cullen was possibly abandoned by his mother, and reared by a woman named Mrs. Porter, who was probably his paternal grandmother. Porter brought young Countee to Harlem when he was nine. She died in 1918. No known reliable information exists of his childhood until 1918 when he was taken in, or adopted, by Reverend and Mrs Frederick A. Cullen of Harlem, New York City. The Reverend was the local minister, and founder, of the Salem Methodist Episcopal Church.In additon Countee Cullen was a very important man in the Harlem Renaissance. He was successful writing many poems that we familiarized ourselves with today and for many years to come. DeWitt Clinton High School At some point, Cullen entered the DeWitt Clinton High School in Manhattan. He excelled academically at the school while emphasizing his skills at poetry and in oratorical contest. At DeWitt, he was elected into the honor society, editor of the weekly newspaper, and elected vice-president of his graduating class. In January 1922, he graduated with honors in Latin, Greek, Mathematics, and French. New York University and Harvard University After graduating high school, he entered New York University (NYU). In 1923, he won second prize in the Witter Bynner undergraduate poetry contest, which was sponsored by the Poetry Society of America, with a poem entitled The Ballad of the Brown Girl. At about this time, some of his poetry was promulgated in the national periodicals Harper's, Crisis, Opportunity, The Bookman, and Poetry. The ensuing year he again placed second in the contest and finally winning it in 1925. Cullen competed in a poetry contest sponsored by Opportunity. and came in second with To One Who Say Me Nay, while losing to Langston Hughes' The Weary Blues. Sometime thereafter, Cullen graduated from NYU as one of eleven students selected to Phi Beta Kappa. Cullen entered Harvard in 1925, to pursue a masters in English, about the same time his first collection of poems, Color, was published. Written in a careful, traditional style, the work celebrated black beauty and deplored the effects of racism. The book included "Heritage" and "Incident", probably his most famous poems. "Yet Do I Marvel", about racial identity and injustice, showed the influence of the literary expression of William Wordsworth and William Blake, but its subject was far from the world of their Romantic sonnets. The poet accepts that there is God, and "God is good, well-meaning, kind", but he finds a contradiction of his own plight in a racist society: he is black and a poet. Cullen's Color was a landmark of the Harlem Renaissance. He graduated with a masters degree in 1926. Professional Career This 1920s artistic movement produced the first large body of work in the United States written by African Americans. However, Cullen considered poetry raceless, although his 'The Black Christ' took a racial theme, lynching of a black youth for a crime he did not commit. Countee Cullen was very secretive about his life. His real mother did not contact him until he became famous in the 1920s. The movement was centered in the cosmopolitan community of Harlem, in New York City. During the 1920s, a fresh generation of writers emerged, although a few were Harlem-born. Other leading figures included Alain Locke (The New Negro, 1925), James Weldon Johnson (Black Manhattan, 1930), Claude McKay (Home to Harlem, 1928), Hughes (The Weary Blues, 1926), Zora Neale Hurston (Jonah's Gourd Vine, 1934), Wallace Thurman (Harlem: A Melodrama of Negro Life, 1929), Jean Toomer (Cane, 1923) and Arna Bontemps (Black Thunder, 1935). The movement was accelerated by grants and scholarships and supported by such white writers as Carl Van Vechten. He worked as assistant editor for Opportunity magazine, where his column, "The Dark Tower", increased his literary reputation. Cullen's poetry collections The Ballad of the Brown Girl (1927) and Copper Sun (1927) explored similar themes as Color, but they were not so well received. Cullen's Guggenheim Fellowship of 1928 enabled him to study and write abroad. He met Nina Yolande Du Bois, daughter of W.E.B. DuBois, the leading black intellectual. At that time Yolande was involved romantically with a popular band leader. Between the years 1928 and 1934, Cullen traveled back and forth between France and the United States. Cullen married Yolande DuBois in April 1928. The marriage was the social event of the decade, but the marriage did not fare well, and he divorced in 1930. It is rumored that Cullen was a homosexual, and his relationship with Harold Jackman was a significant factor in the divorce. Jackman was a teacher whom Van Vechten had used as a model in his novel Nigger Heaven (1926). By 1929 Cullen had published four volumes of poetry. The title poem of The Black Christ and Other Poems (1929) was criticized for the use of Christian religious imagery - Cullen compared the lynching of a black man to the crucification of Jesus. As well as writing books himself, Cullen promoted the work of other black writers. But by 1930 Cullen's reputation as a poet waned. In 1932 appeared his only novel, One Way to Heaven, a social comedy of lower-class blacks and the bourgeoisie in New York City. From 1934 until the end of his life, he taught English, French, and creative writing at Frederick Douglass Junior High School in New York City. During this period, he also wrote two works for young readers, The Lost Zoo (1940), poems about the animals who perished in the Flood, and My Lives and How I Lost Them, an autobiography of his cat. In the last years of his life, Cullen wrote mostly for the theatre. He worked with Arna Bontemps to adapt his 1931 novel, God Sends Sunday into St. Louis Woman (1946, publ. 1971) for the musical stage. Its score was composed by Harold Arlen and Johnny Mercer, both white. The Broadway musical, set in poor black neighborhood in St. Louis, was criticized by black intellectuals for creating a negative image of black Americans. Cullen also translated the Greek tragedy Medea by Euripides, which was published in 1935 as The Medea and Some Poems with a collection of sonnets and short lyrics. In 1940, Cullen married Ida Mae Robertson, whom he had known for ten years.)

The Best Poem Of Countee Cullen

Incident

Once riding in old Baltimore,

Heart-filled, head-filled with glee,

I saw a Baltimorean

Keep looking straight at me.

Now I was eight and very small,

And he was no whit bigger,

And so I smiled, but he poked out

His tongue, and called me, 'Nigger.'

I saw the whole of Baltimore

From May until December;

Of all the things that happened there

That's all that I remember.

Countee Cullen Comments

Digital audio versions are sad. Perhaps the many fans of Poem Hunter could be called upon to lend their voices to creating audio recordings of the poems that would contained real resonance and prosody.

This is quite a nice poem that has a lot many metaphors. I enjoyed them a lot.