Merlinda Carullo Bobis

Merlinda Carullo Bobis Poems

it is not bare tonight,

this black wall.

it suddenly wore a tiny star,

...

i love too beautifully today,

as if tomorrow I will die.

i even tie my hair from cliff to cliff

...

the blind are showing movies

in the plaza

so the deaf are gathering

in the plaza

so the mute can debate

in the plaza

the fate

of one beloved nation

...

Once upon a time in Bikol, Pilipino, English —

we tell it over and over again.

Digde ini nagpopoon. Anum na taon ako, siguro lima.

Si Lola nag-iistorya manongod sa parahabon nin kasag

Na nagtatago sa irarom kan kama.

Dito ito nagsisimula. Anim na taon ako, siguro lima.

Si Lola nagkukuwento tungkol sa magnanakaw ng alimango

na nagtatago sa ilalim ng kama.

This is where it begins. I am six years old, perhaps five.

Grandmother is storytelling about the crab-stealer

hiding under the bed. Each story-word crackles

under the ghost's teeth, infernal under my skin. I shiver.

But perhaps this is where it begins.

Grandfather teasing me with that lady in the hills

walking into his dream, each time a different

colour of dress, a different attitude under my skin.

I am bereft of constancy, literal

at six years old, perhaps five.

Or, this is where it begins.

Mother reviewing for her college Spanish exam:

‘Ojos.'

‘Labios.'

‘Manos.'

Suddenly also under my skin, long before I understood

‘Eyes': how they conjure ghosts under the bed,

‘Lips': how they make ghosts speak,

‘Hands': how they cannot be silent.

I remember too Father gesturing, invoking

once upon a time. This is where it begins.

Story, word, gesture

all under my skin. At six years old, perhaps five.

And so this poem is for my father, mother,

grandmother, grandfather and all the storytellers,

the conjurers who came before us. They made us shiver

not just over crab-stealers hiding under the bed

or a lady uncertain of her garb. They made us shiver

also over faith, over tenderness.

Or that little tickle when a word hits a hidden

crevice in the ear. Just air

heralding the world or worlds that we think

we dream up alone.

No, storytelling is not lonely,

not as we claim—in our little rooms lit only

by a lamp or a late computer glow.

Between the hand and the pen, or the eye and the screen,

they have never left, they who ‘storytold' before us,

they who are under our skin.

Perhaps they even conjured us, but not alone.

Storytelling, all our eyes collect into singular seeing,

our lips test one note over and over again,

our hands follow each other's arc, each sweep of resolve.

Eyes, lips, hands conjoined: the umbilical cord restored.

...

when fringe of lips

and tips of hair

run a sweet fever

at one o'clock in the morning

when a shameless nipple

stares like a hot-hard eye

at one o'clock in the morning

when the little finger

and the little toe

burn holes on wind and earth

it is the hour of the gipsy heart

vagrant of my lover's body

cul-de-sac of belly

avenue of thigh

still dark and silent

at one o'clock in the morning

when the whole world sleeps

save me who waits

for the double somersault

of the heart

...

I, too, can love you

in my dialect, you know,

punctuated with cicadas

and their eternal afternoons —

...

how easily a speck of bird

shatters the evenness of skies—

she peers, stunned, from cell 22

that such dumb minuteness

can shake the earth

...

When I met you,

you even wished to learn

how to laugh in my dialect.

Between the treble of bees

and the deep bass of water buffalos

on tv's ‘World Around Us'.

Between the husk and grain of rice

from an Asian shop.

Between my palms

joined earnestly

in prayer,

you searched for a timbre

so quaint,

you'd have to train your ears

forever, you said.

And when I told you how we village girls

once burst the moon with giggles,

you piped, ‘That must have been

a thrilling sound,

peculiar, ancient

and really cool—

can't you do that again?'

...

every night from work,

she proceeds to test for damp

the lingerie redundant on the line.

the wash are shadows of other hangings;

they need to be tucked away

like virtue nightly slipped

into an old rose vanity.

she shuts her windows tightly

from a fire-wall never higher than her grim

stare, and begins to strip away

the opaqueness of the day.

she resists the sin of a lone mirror;

it might reveal her luminous.

a monotone of rice and fish

is laid out then—the voyeur yellow bulb

is asked to dinner. it's their affair

to have it hug her limbs,

and gentle them to grace.

she squints in welcome

of its savage repetition on her face.

nightcap follows, a glass of milk

for gut-wounds. they nag for feasts

that hush with sleep.

tucked between eight and nine,

the willing mattress holds her down,

its weight unstirring as a mother's arms.

she, too, does not stir,

except on moments when her hands flail,

ever slightly, to toss aside

this mother's clasp

in dreams of maybe younger arms.

but they only flail-flop

back to her breast

like some impotent reliquary.

her mouth half-opened

cups the darkness for posterity.

so she does not hear the rustle,

the young wife's skirt,

the fabric-sigh that ransoms

the next room from shadows.

...

for Mama Ola

the sea clings

to the roof of my mouth,

but the tide of my heart

cannot swell.

only this salt-taste,

this dumb remembering,

sharp as the flavour

of fish dried on the beach.

...

Today, you span the far mountains

with an arm and say,

‘This I offer you—

all this blue sweat

of eucalypt.'

Then you teach me

how to startle kookaburras

in my throat

and point out Orion

among the glowworms.

I, too, can love you

in my dialect, you know,

punctuated with cicadas

and their eternal afternoons:

‘Mahal kita. mahal kita.'

I can even save you monsoons,

pomelo-scented bucketfuls

to wash your hair with.

And, for want of pearls,

I can string you the whitest seeds

of green papayas

then hope that, wrist to wrist,

we might believe again

the single rhythm passing

between pulses,

even when pearls

become the glazed-white eyes

of a Bosnian child

caught in the cross-fire

or when monsoons cannot wash

the trigger-finger clean

in East Timor

and when Tibetans

wrap their dialect

around them like a robe

lest Orion grazes them

from a muzzle.

Yes, even when among the Sinhalese

the birds mistake the throat

for a tomb

as gunsmoke lifts

from the Tamil mountains,

my tongue will still unpetrify

to say,

‘Mahal kita. Mahal kita.'

...

take me not

in mid-winter,

only to thaw the frost

of your old bones,

imagining how stallions rear

in the outback,

hooves raised to this august light,

kakaibang liwanag,

kasimputla't kasinglamig

ng hubad na peras.¹

but take me

on a humid afternoon

made for siesta,

when my knees almost ache

from daydreaming of mangoes,

tree-ripe

and just right,

at higit sa lahat

mas matamis, makatas

kaysa sa unang halik ng mansanas.²

—————————

¹‘alien light,

as pale and cold

as a naked pear'

plucked from my tongue you have wrapped

in a plastic bag with the $3 mango

from woolworths

while i conjured an orchard

from back home—mangoes gold and not for sale, and

²‘above all,

sweeter, more succulent

than the first kiss of the apple.'

...

I bring you words freshly

prised loose from my wishbone.

Mahal, oyayi, halakhak, lungkot, alaala.

Mate those lips,

then heave a wave in the throat

and lull the tip of the tongue

at the roof of the mouth.

Mahal. mahal. mahal.

‘Love, love, love'—let me,

in my tongue.

Then I'll sing you a slumber tale.

Oyaiiyaiiyaiiyayiiiii— once,

mother pushed the hammock

away—oyaiiyaiiyaiiyayiiiii,

the birthstrings severed from her wrist

when I married

an Australian.

So now I can laugh with you.

Halakhak! How strange.

Your kookaburras roost in my windpipe

when I say, ‘Laughter!'

as if feathering a new word.

Halakhak-k-k-k-kookaburra!

But if suddenly you pucker

the lips—lung—

as if you were about to break

into tears or song — watch out,

the splinter cuts too far too much—lunggggggg—

unless withdrawn—kot—

in time. Lungkot.

Such is our word for ‘sadness'.

Ah! For relief, release, wonder or peace

in any tongue. ‘Ah!'

of the many timbres;

this is how remembering begins—ah!—

and is repeated—lah!-ah!-lah!

Alaala. This is our word for ‘memory'.

How it forks

like a wishbone.

Mahal, oyayi, halakhak, lungkot, alaala.

How they flow

East-West-East-West-East

in one bone wishing

it won't break.

...

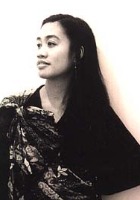

Merlinda Carullo Bobis Biography

Merlinda Carullo Bobis is a contemporary Philippine-Australian writer and academic. Born in Legaspi City, in the Philippines province of Albay, Merlinda Bobis attended Bicol University High School then completed her B.A. at Aquinas University in Legaspi City. She holds post-graduate degrees from the University of Santo Tomas and University of Wollongong, and now lives in Australia. Written in various genres in both Filipino and English, her work integrates elements of the traditional culture of the Philippines with modern immigrant experience. Also a dancer and visual artist, Bobis currently teaches at Wollongong University. Her play Rita's Lullaby was the winner of the 1998 Awgie for Best Radio Play and the international Prix Italia of the same year; in 2000 White Turtle won the Steele Rudd Award for the Best Collection of Australian Short Stories and the 2000 Philippine National Book Award. Most recently, in 2006, she has received the Gintong Aklat Award (Golden Book Award, Philippines) for her latest novel Banana Heart Summer, from the Book Development Association of the Philippines.)

The Best Poem Of Merlinda Carullo Bobis

From Cell Nine

Mula Sa Selda Nuwebe

hindi hubad ngayong gabi

itong pader na itim.

nagbihis bigla ng munting bituin,

nang butasin ng iyong titig

ang lamig ng kongkreto—

sige, kukuskusin ko ng mata ang siwang

na para bang amuleto,

bukas, bukas,

mahuhusto dito

ang humuhulagpos tang mundo.

From Cell Nine

it is not bare tonight,

this black wall.

it suddenly wore a tiny star,

when you stared a hole

on the cold concrete—

all right, i shall rub the crack with the eye

as if it were some amulet.

tomorrow, tomorrow,

our world struggling to be free

will pull through here.