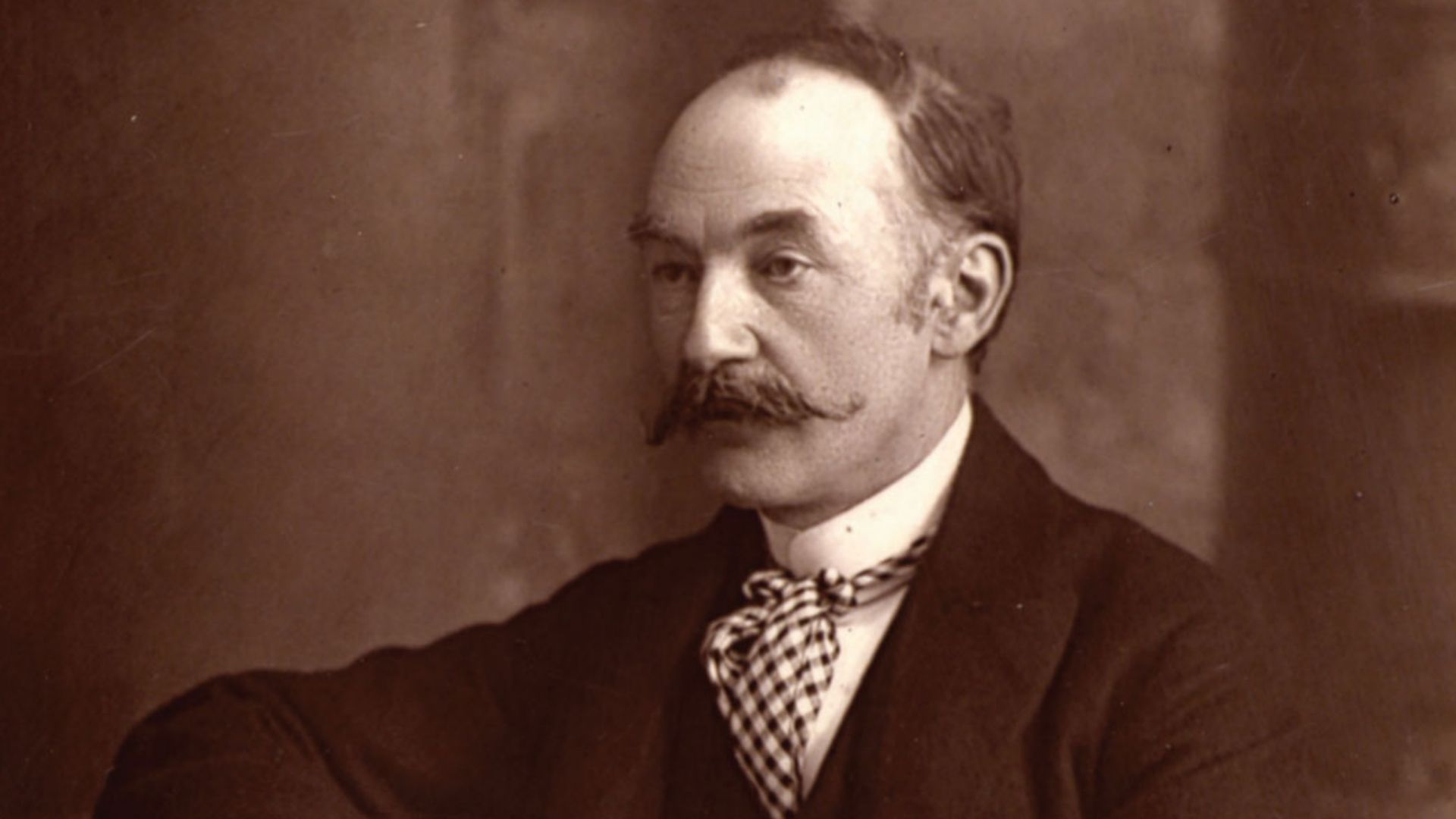

Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy Poems

I said to Love,

"It is not now as in old days

When men adored thee and thy ways

All else above;

...

Between us now and here -

Two thrown together

Who are not wont to wear

Life's flushest feather -

...

You did not come,

And marching Time drew on, and wore me numb.

Yet less for loss of your dear presence there

Than that I thus found lacking in your make

...

How great my grief, my joys how few,

Since first it was my fate to know thee!

- Have the slow years not brought to view

How great my grief, my joys how few,

...

I need not go

Through sleet and snow

To where I know

She waits for me;

...

I leant upon a coppice gate,

When Frost was spectre-gray,

And Winter's dregs made desolate

The weakening eye of day.

...

They throw in Drummer Hodge, to rest

Uncoffined -- just as found:

His landmark is a kopje-crest

That breaks the veldt around:

...

AS evening shaped I found me on a moor

Which sight could scarce sustain:

The black lean land, of featureless contour,

Was like a tract in pain.

...

Had he and I but met

By some old ancient inn,

We should have set us down to wet

Right many a nipperkin!

...

I

I have lived with shades so long,

And talked to them so oft,

...

South of the Line, inland from far Durban,

A mouldering soldier lies- your countryman.

Awry and doubled up are his gray bones,

And on the breeze his puzzled phantom moans

...

WE stood by a pond that winter day,

And the sun was white, as though chidden of God,

And a few leaves lay on the starving sod,

--They had fallen from an ash, and were gray.

...

I--The Tragedy

She sits in the tawny vapour

That the City lanes have uprolled,

...

She wore a 'terra-cotta' dress,

And we stayed, because of the pelting storm,

Within the hansom's dry recess,

Though the horse had stopped; yea, motionless

...

Through vaults of pain,

Enribbed and wrought with groins of ghastliness,

I passed, and garish spectres moved my brain

To dire distress.

...

I

In Casterbridge there stood a noble pile,

Wrought with pilaster, bay, and balustrade

...

YOUR troubles shrink not, though I feel them less

Here, far away, than when I tarried near;

I even smile old smiles--with listlessness--

Yet smiles they are, not ghastly mockeries mere.

...

The day is turning ghost,

And scuttles from the kalendar in fits and furtively,

To join the anonymous host

Of those that throng oblivion; ceding his place, maybe,

...

Only a man harrowing clods

In a slow silent walk

With an old horse that stumbles and nods

Half asleep as they stalk.

...

When the Present has latched its postern behind my tremulous stay,

And the May month flaps its glad green leaves like wings,

Delicate-filmed as new-spun silk, will the neighbours say,

'He was a man who used to notice such things'?

...

Thomas Hardy Biography

Thomas Hardy was born June 2, 1840, in the village of Upper Bockhampton, located in Southwestern England. His father was a stone mason and a violinist. His mother enjoyed reading and relating all the folk songs and legends of the region. Between his parents, Hardy gained all the interests that would appear in his novels and his own life: his love for architecture and music, his interest in the lifestyles of the country folk, and his passion for all sorts of literature. At the age of eight, Hardy began to attend Julia Martin's school in Bockhampton. However, most of his education came from the books he found in Dorchester, the nearby town. He learned French, German, and Latin by teaching himself through these books. At sixteen, Hardy's father apprenticed his son to a local architect, John Hicks. Under Hicks' tutelage, Hardy learned much about architectural drawing and restoring old houses and churches. Hardy loved the apprenticeship because it allowed him to learn the histories of the houses and the families that lived there. Despite his work, Hardy did not forget his academics: in the evenings, Hardy would study with the Greek scholar Horace Moule. In 1862, Hardy was sent to London to work with the architect Arthur Blomfield. During his five years in London, Hardy immersed himself in the cultural scene by visiting the museums and theaters and studying classic literature. He even began to write his own poetry. Although he did not stay in London, choosing to return to Dorchester as a church restorer, he took his newfound talent for writing to Dorchester as well. From 1867, Hardy wrote poetry and novels, though the first part of his career was devoted to the novel. At first he published anonymously, but when people became interested in his works, he began to use his own name. Like Dickens, Hardy's novels were published in serial forms in magazines that were popular in both England and America. His first popular novel was Under the Greenwood Tree, published in 1872. The next great novel, Far from the Madding Crowd (1874) was so popular that with the profits, Hardy was able to give up architecture and marry Emma Gifford. Other popular novels followed in quick succession: The Return of the Native (1878), The Mayor of Casterbridge (1886), The Woodlanders (1887), Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1891), and Jude the Obscure (1895). In addition to these larger works, Hardy published three collections of short stories and five smaller novels, all moderately successful. However, despite the praise Hardy's fiction received, many critics also found his works to be too shocking, especially Tess of the D'Urbervilles and Jude the Obscure. The outcry against Jude was so great that Hardy decided to stop writing novels and return to his first great love, poetry. Over the years, Hardy had divided his time between his home, Max Gate, in Dorchester and his lodgings in London. In his later years, he remained in Dorchester to focus completely on his poetry. In 1898, he saw his dream of becoming a poet realized with the publication of Wessex Poems. He then turned his attentions to an epic drama in verse, The Dynasts; it was finally completed in 1908. Before his death, he had written over 800 poems, many of them published while he was in his eighties. By the last two decades of Hardy's life, he had achieved fame as great as Dickens' fame. In 1910, he was awarded the Order of Merit. New readers had also discovered his novels by the publication of the Wessex Editions, the definitive versions of all Hardy's early works. As a result, Max Gate became a literary shrine. Hardy also found happiness in his personal life. His first wife, Emma, died in 1912. Although their marriage had not been happy, Hardy grieved at her sudden death. In 1914, he married Florence Dugale, and she was extremely devoted to him. After his death, Florence published Hardy's autobiography in two parts under her own name. After a long and highly successful life, Thomas Hardy died on January 11, 1928, at the age of 87. His ashes were buried in Poets' Corner at Westminster Abbey.)

The Best Poem Of Thomas Hardy

"I Said To Love"

I said to Love,

"It is not now as in old days

When men adored thee and thy ways

All else above;

Named thee the Boy, the Bright, the One

Who spread a heaven beneath the sun,"

I said to Love.

I said to him,

"We now know more of thee than then;

We were but weak in judgment when,

With hearts abrim,

We clamoured thee that thou would'st please

Inflict on us thine agonies,"

I said to him.

I said to Love,

"Thou art not young, thou art not fair,

No faery darts, no cherub air,

Nor swan, nor dove

Are thine; but features pitiless,

And iron daggers of distress,"

I said to Love.

"Depart then, Love! . . .

- Man's race shall end, dost threaten thou?

The age to come the man of now

Know nothing of? -

We fear not such a threat from thee;

We are too old in apathy!

Mankind shall cease.--So let it be,"

I said to Love.

Thomas Hardy Comments

To every failure there’s Hell and all success is heavenly. - Arthur Tugman

Come hither or go yon in your quest for success or else be content to dither in failure. - Arthur Tugman Come hither or go yon in your quest for success or else be content to dither in failure. - Arthur Tugman

I like. I am going to use it to teach styles in Form three class. beautiful. I wish I could get an analysis from you before I try doing it my way.

Have always loved his different forms of literature especially tess of the d'urbervilles

Thomas Hardy Quotes

And yet to every bad there is a worse.

And ghosts then keep their distance; and I know some liberty.

It is difficult for a woman to define her feelings in language which is chiefly made by men to express theirs.

The value of old age depends upon the person who reaches it. To some men of early performance it is useless. To others, who are late to develop, it just enables them to finish the job.

Of course poets have morals and manners of their own, and custom is no argument with them.

It is safer to accept any chance that offers itself, and extemporize a procedure to fit it, than to get a good plan matured, and wait for a chance of using it.

A resolution to avoid an evil is seldom framed till the evil is so far advanced as to make avoidance impossible.

A lover without indiscretion is no lover at all. Circumspection and devotion are a contradiction in terms.

Some folk want their luck buttered.

Like the British Constitution, she owes her success in practice to her inconsistencies in principle.

Everybody is so talented nowadays that the only people I care to honour as deserving real distinction are those who remain in obscurity.

Poetry is emotion put into measure. The emotion must come by nature, but the measure can be acquired by art.

My opinion is that a poet should express the emotion of all the ages and the thought of his own.

That man's silence is wonderful to listen to.

My argument is that War makes rattling good history; but Peace is poor reading.

Once victim, always victim—that's the law!

That cold accretion called the world, which, so terrible in the mass, is so unformidable, even pitiable, in its units.

Patience, that blending of moral courage with physical timidity.

That cold accretion called the world, which, so terrible in the mass, is so unformidable, even pitiable, in its units.

Patience, that blending of moral courage with physical timidity.

Ethelberta breathed a sort of exclamation, not right out, but stealthily, like a parson's damn.

Ethelberta breathed a sort of exclamation, not right out, but stealthily, like a parson's damn.

Dialect words—those terrible marks of the beast to the truly genteel.

Hi Thomas...........Hello...... How are you? this is Maricel from Philippines and i would like to tell you that you are very good and great so much in your poet......i like it very much........i hope you can tell me what is your secret there how to write a poet like that you wrote....ok...heheh joke only....cus you know i dont have yet one poet that i write here, its great for you........well anyway thomas thanks again for your very nice poet........ok takecare there always and have a nice to day to you there and to all...............see you! ! ! always, Maricel