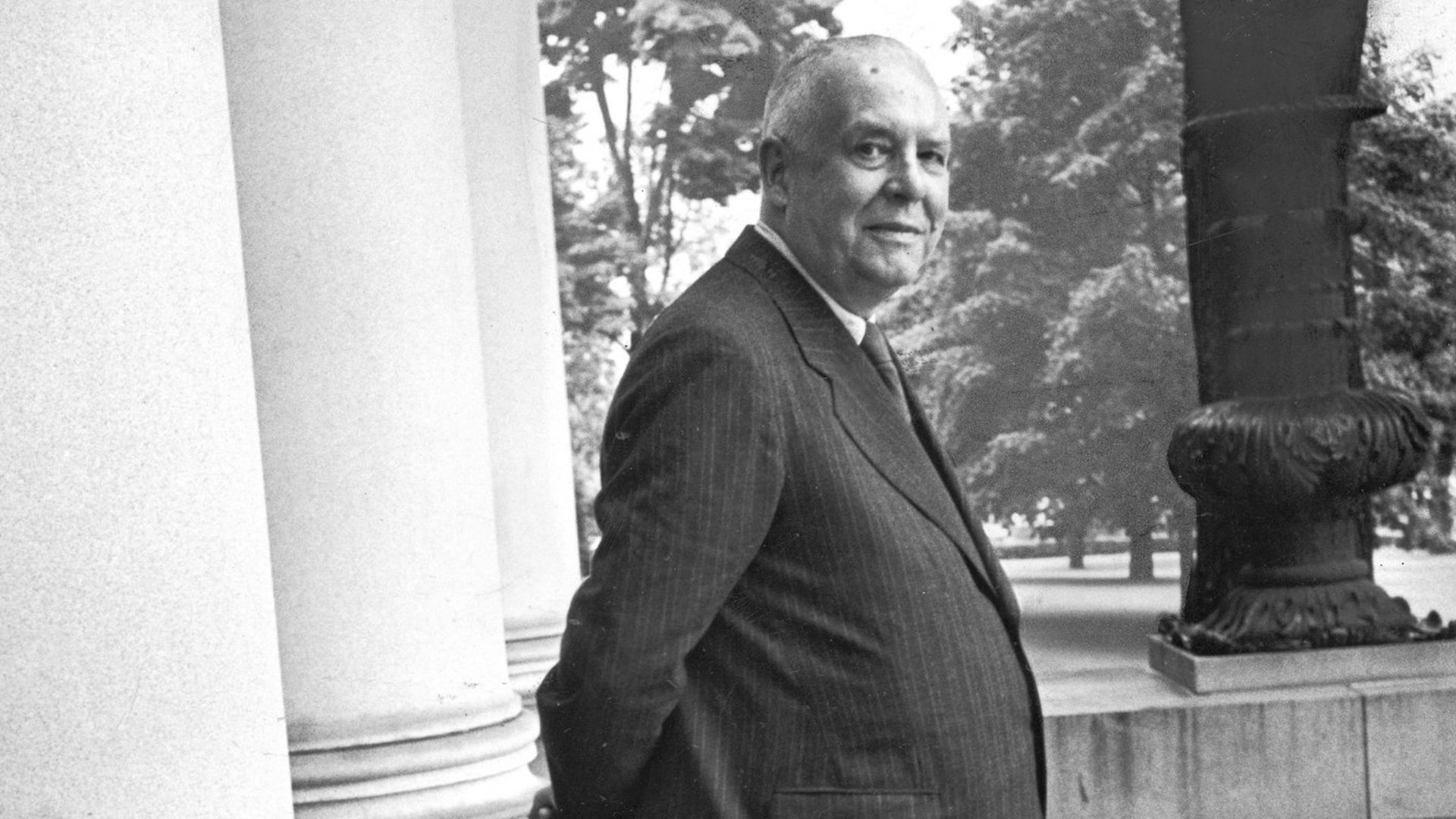

Of Modern Poetry Poem by Wallace Stevens

Of Modern Poetry

The poem of the mind in the act of finding

What will suffice. It has not always had

To find: the scene was set; it repeated what

Was in the script.

Then the theatre was changed

To something else. Its past was a souvenir.

It has to be living, to learn the speech of the place.

It has to face the men of the time and to meet

The women of the time. It has to think about war

And it has to find what will suffice. It has

To construct a new stage. It has to be on that stage,

And, like an insatiable actor, slowly and

With meditation, speak words that in the ear,

In the delicatest ear of the mind, repeat,

Exactly, that which it wants to hear, at the sound

Of which, an invisible audience listens,

Not to the play, but to itself, expressed

In an emotion as of two people, as of two

Emotions becoming one. The actor is

A metaphysician in the dark, twanging

An instrument, twanging a wiry string that gives

Sounds passing through sudden rightnesses, wholly

Containing the mind, below which it cannot descend,

Beyond which it has no will to rise.

It must

Be the finding of a satisfaction, and may

Be of a man skating, a woman dancing, a woman

Combing. The poem of the act of the mind.

he probably just writing and writing whatever comes to his mind

It has no will to rise! ! Thanks for sharing this poem with us.

Yes poetry changes time to time, splendidly written verse is this. It’s a poets poem.

Love the way it expressed the difference between the historic poetry and the morden poetry.., , great write..,

Love this poem. It gave me chills it touched apart of me that I've not known just by reading a poem online.

As Daniel Brick correctly notes in his post, this poem is meant to address what has historically become known as modernist art, not merely what is modern and contemporary in time. There was an upheaval in society's perception of the speed at which world events took place beginning roughly with the industrial revolution and really coming to a head with the horrors of the great war (World War I) . Stevens argues in this poem that the pretty pictures, the expected rhythms and rhymes are no longer adequate to describe the events and emotions of this modern world. You cannot rely on the old scripts and simply repeat them with new variations. The way we live in the world became fundamentally different and the art that could apply and appeal to these new circumstances had to be new. Had to be addressed to the actual living understanding that takes place in a mind in the act of being present and finding a way to conduct itself amongst the newest of this world and its advancements. An art form, a work of art itself has to be as alive and in the moment as the author and the audience both. To achieve that symbiosis is the goal. Not by looking back at the old forms and the old works, but by perspicaciousness requiring insight and not a little bit work and active interaction. That investment is paid off by subjective internalization of the work. A transcendence that suffices to carry us forward and anneal some the wounds of ignorance and division. This is one Stevens more didactic poems and from that angle not really one of his most satisfying, in my opinion. But it holds keys to reading some of the seemingly more opaque and metaphorical pieces he wrote, because just about everything he ever published touches on the theme explicated here.

Denis, it might be helpful to you to see that where Wallace Stevens was a Modernist poet it sounds to me that your avant gardist friend is most likely a Post-Modernist. These are historical art movements and must not be confused with any notion of contemporaneous, recent chronological placement. There are still artists working within the Modernist framework of thought, which generally speaking still accepts the ideas of science and consensus of thought as a necessary and expedient means of navigating our world. Dialogue and conversation are not only possible but preferable under this aesthetic. There are universal truths that bind the Modernists together and help them to cohere. Post-Modernism, arising partly in response to the horror of World War II and the unthinkable atrocities that occurred then lead to an aesthetic response that reflected the idea that maybe we don't know how to talk to each other, maybe there are no universal truths to bind us, that are faith in community is ill-founded and all experience is first and foremost personal. But there is still an implicit acknowledgement of our communal plight in the fact that these Post-Modernist artists are still creating work for an audience and in that there is the idea of communication. It's just that there's a searching for a new model independent of the conventions that seem to always lead humanity back to atrocity. It is still hopeful, it is still conversant, it is still a galvanizing force.

Thanks, Lantz, for confirming my insight into Stevens's us of the word MODERN. With Stevens I am always a bit uncertain of my interpretation even though I've been reading his work since 1965. Sic! After his death Ezra Pound wrote Wm. Carlos Williams. Will we understand what he was saying now he's gone? He did not sound hopeful. Sic. But you can move securely through his puzzling poems.

This poem has not been translated into any other language yet.

I would like to translate this poem

On a literal level, this poem can be very confusing. It speaks about a poem “of a mind in the act of finding/ What will suffice.” IMHO, Stevens is not talking about a poem in the act of finding, he is addressing a mind in the act of finding. Of course, the ambiguity is deliberate. Grammatically, one could follow down, substituting either “poem” or “mind” for “it, ” and one would be correct using either. Still, how good could a poem be if it is only looking for what will “suffice? ” Shouldn’t a poem reach for excellence instead of something that will merely suffice? Similarly, shouldn’t a mind stretch toward excellence? The answer of course is yes, we should—we must—strive toward excellence. But along the way, we must first find and accept what will “suffice.” It appears to me the “mind in the act of finding” is searching for truth, solidity, comfort, freedom, certainty—all the things that philosophy and theology have sought since the time of Socrates. In our relativistic time, what will suffice for truth? What will grant us comfort and yet allow us freedom? In previous eras, the “finding” was not necessary. The church, the government, society, or some other institution, provided what would suffice. One didn’t need to think about such things. One accepted the prevailing doctrine, the faith of our fathers. Now, however, that has changed. We must construct a new stage, we must be on that stage, and we must “speak words that in the ear, /In the delicatest ear of the mind, repeat, /Exactly, that which it wants to hear, at the sound /Of which, an invisible audience listens, /Not to the play, but to itself…” The philosophy, the code we find for ourselves, must fit. It must appeal to that “delicatest ear of the mind.” This is the measure of what will “suffice.” It must resonate with us, and produce “Sounds passing through sudden rightnesses…” In short, “It must /Be the finding of a satisfaction, and may /Be of a man skating, a woman dancing, a woman /Combing. The poem of the act of the mind.” What will suffice may come in the simplicity of life itself; in the emotions of daily living.